My father build his own auto repair shop shortly after the war. It was quite a grand structure with an impressively engineered single barrel vault made of timber, and with room enough for six active repair bays. In front was an office, but as my mother performed official tasks and preferred to work at home, it was never used. Instead they rented it to Fred Brackenbury who repaired radios, then a bit later, televisions. Brackenbury had a sign painted over his entrance. Dad never painted a sign, but by the time I was about eight, I was pretty convinced that he was waiting to put one up that said “Zarko and Son”.

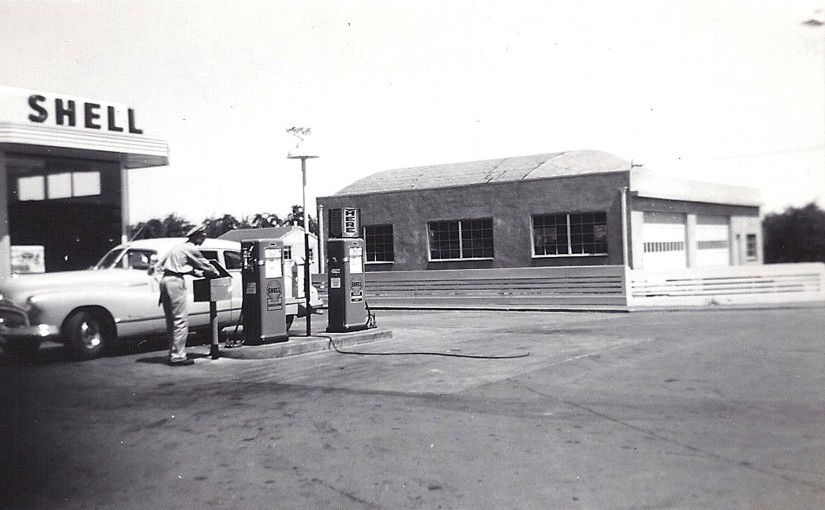

My parents bought the lot on the corner of Mathilda Avenue and El Camino Real in 1945. There was a house on it, built in 1925, and a large garden, probably a few fruit trees. They moved the house a half block away not long after to free the property for commercial use. My mother rode inside the breakfast room during the move, because as she said, “When else will I have the chance to ride a house?” She tried to get Dad to join her, but he thought that would be silly.

My father loved mechanics like I loved theatre. In about 1920, when they were in their teens, he and his brother, Tony (aka Bill) created a functioning motor vehicle out of discarded farm equipment. His first job was as a cleaner at Redwine Ford dealership in Mountain View. Maybe he couldn’t get his hands greasy pushing a broom, but at least he would be in the company of those who did.

By the end of the decade, he had formed a business partnership with a man named Frazier, and together they opened a Ford dealership of their own on Sunnyvale’s main street. Not bad for a farmer’s son. I’m sure that Frazier had a first name, but even though he was talked about regularly in our household, and years after the partnership dissolved in deference to performing war-essential work, I don’t remember ever hearing it. Willard! Okay, but hearing it was rare.

I suspect that being both a dealership and a repair shop encouraged a certain degree of order and cleanliness when there was a Frazier and Zarko, but once it was Pete Zarko’s Garage, he could revel in grease, and he did. I loved it, too, as a kid, all that caked, black goo. He’d put me to work scraping pans of some automotive purpose, and it was so satisfying to feel the thick resistance of a heavy layer of coagulated oil give way to the tool’s stout blade. Waste oil, and I believe even the goo, was stored in large cans and picked up weekly to be recycled. Oil was the gold of his enterprise, and he treated it with serious respect. He also thew the stuff that was too filled with particulate matter to be cleaned onto the ground behind the shop so he wouldn’t be bothered with weeds. I imagine that when the City turned the corner into a park, they had some serious environmental cleanup to do.

So, it was at about the age of eight that he first began inviting me to work with him when the family Ford needed mechanical attention. We started with simple things like cleaning spark plugs and distributors. Eventually, he taught me how to adjust timing, clean carburetors, change oil, and top off brake fluid. By the time I was twelve I was under the car with him when the clutch needed changing, adjusting brake drums, and doing other gloriously greasy work that I remember the fun of, but not the purpose.

Still, I knew in my gut that the sign Dad wanted to paint wasn’t going to happen. I enjoyed those times peering into engines and rolling around under a car. When he gave me clean up jobs, I did my best to exceed expectations, and tried my best to hide my disappointment at how quickly everything got messy again. And I admired the garage, loved my father, and was proud of his good reputation. But I didn’t relish mechanics. Didn’t even really like riding in a car all that much, let alone fixing one.

I started taking walks as soon as it was physically possible. I still remember exiting Grandma Zarko’s yard on the Waverly Street side, pushing open the white gate, and heading for parts unknown. A bemused neighbor asked where I was off to.

“I’m taking a walk,” I proclaimed. And I accomplished three houses before my mother discovered I was gone and came running after me. I walked to school in first grade. My grandmother’s house was a short distance from Adair Elementary, so it began with lunches, and quickly advanced to trooping home on my own, as well.

I vividly remember hiking after school – it had to have been first or second grade, because Mom was still driving the 1936 Ford Victoria – about to cross Iowa Street, when she pulled up, rolled down her window, and with a radiant smile offered me a ride.

“No! Can’t you see I’m walking!?” And I truculently crossed Iowa and stomped the few blocks home.

My love of walking is in my DNA, I guess. The same way that love of a humming engine was in Dad’s.

So, here we are, I’m maybe seventeen, and we’re giving the car a tune up. I am perhaps not pretending enthusiasm as strongly as I may have done a few years prior. I had been strongly lured by a theatrical siren, and grease was losing its charm. I harbored hopes that something besides my saying it would convince my father that I was not meant to follow in his footsteps.

We drain the oil pan. I take it to a waiting recycling barrel. Dad hands me the five-quart oil can to be filled from the new-oil barrel across the shop next to the restroom. I go. I fill it. The oil is transferred to the Ford engine.

“Let’s top this sucker off just a little, I think it wants another half pint.” That’s his polite way of saying that I’d not filled the can. I sulk back to the new-oil barrel.

“Oh, my god! Oh, my god! Oh, my god!”

That was me. My Dad never got excited like that. However, this one time he did join me at trot.

I had left the tap open. There were now several gallons of liquid gold covering the floor from parts shelves to grease rack. Dad picked up two sheets of tin, inserted a funnel with a filter into the barrel, and without saying a word or casting blame, we scooped up as much oil as we could manage. The rest was sopped up under a layer of sawdust, and swept into a trash can.

I could see the sign saying Zarko and Son falling into a disorderly heap in front of my father’s garage. It wasn’t a sin, what I’d just done, but it sure as heck was a signal, and Dad read it as clearly as I had hoped it would.

There were still many hours spent together leaning over fenders and scooting under transmissions, but now we did it because… well, that’s what we did together. When Dad retired early so he could work on his antique autos, he sold the business to his longtime employee, Louie, and no sign of any kind was ever painted for Zarko’s Garage. When Louie retired, the City bought the land, and for a brief period before it was a bank (for a period even briefer) I imagined what an interesting theatre it would make.