When I was growing up, the farthest extent of living memory – that of my grandparents – involved high-button shoes and handlebar mustaches. The present day equivalent involves colorfully striped bell-bottom trousers and, well, handlebar mustaches, and I am of the generation that lives on those far fringes of living memory.

What will follow between now and January 6 – the traditional end of the Christmas season – will be my memories and those of my cousins. The specific holiday is not, to me, all that significant, and only some of the memories will be holiday related. That we gathered to celebrate our family in our family’s way is what ties me to these recollections, and, I hope, will stir reflective memories of your family’s way, in turn.

My dear friend Erika (click for her blog), an American who married Italian and has been living in Orvieto since 1958, observed that Christmas gifts are bulky, take up space, and are hard to carry while juggling a cane and a dog. This year, she would give memories. Memories have none of the aforementioned disadvantages. My aching feet had convinced me that gifting would not be possible this year. Pandemic-related restrictions convinced me further. Erika’s idea of giving memories changed my mind.

Let’s begin with my fifth Christmas Eve. I was the youngest among us, so it was deemed that I should be the one to personally meet Santa Claus. Being only four, I didn’t have a lot to draw on as to what was or was not traditional, but the family gathered at my parents’ house that year – 1953 – the only time I can bring to mind that we were not at my Aunt Marian and Uncle Bill’s. So, even with little precedent, I remember being excited that we were hosting the festivities.

What I don’t recall, but would bet was traditionally observed, was the pre-gift giving meal at my grandmother Zarko’s. The ancestral estate was a five-room farmhouse build in about 1908. It smelled of garlic year around, of quince candy during the winter months, and of Croatian strudel with apples and apricots in the fall. The Christmas smell was boiled cod.

I don’t remember there ever being a Christmas tree, there was no room for one. There was a radio the size of a refrigerator from the 1920’s, a pump organ that no one knew how to play, a glass-fronted hutch filled with dishware extracted from boxes of detergent, china as prizes for choosing the proffered brand. There were butter-block chairs and a settee upholstered in crackling black leather and stuffed with horsehair on top of spiky, spindly springs. The kitchen was dominated by a round oak pedestal table that my mother had found for five dollars, second or third hand during the war, and which she brought home – my folks lived with my grandmother in those days – in the rumble seat of her Model A Ford. Warming the house was a combination wood and gas burning stove with a special tank for hot water. The phone in the hall had a call button that you pushed to gain an operator’s attention so you could vocally tell her the number of the person you wanted to reach, or if you couldn’t remember the number, the name.

On a back porch that always felt like it was about to slide into the vegetable garden behind the house, was a squat cast-iron wood burning stove, the oven door graced with a white porcelain panel that contained a temperature gauge with a black needle. The other half of the porch was glassed-in and home to a perplexing number of coleus plants, spilling over their shelves and onto the floor. There was always a gallon tin of extra virgin olive oil sitting on an oil-saturated side table, the hole poked into its lid stopped up with a bit of a twig. As a kid I imagined the twig was, logically, from an olive tree, but probably not.

Perhaps because they had lived there for so long, my parents always entered through the back porch. Everyone else came in through the front door, a narrow panel precariously placed at the top of four narrow, steep stairs, it sported no handrail, and the screen door opened out. For every festive occasion, lives were risked just to attend dinner.

And every Christmas Eve and Good Friday, Grandma Zarko cooked cod. And at every codfish dinner, my Uncle Bill would quip that to make the stuff eatable required dragging it behind a tractor for two hours, soaking it in acid, pounding it with a hammer, and boiling it overnight. He was exaggerating, but only slightly.

The meal Grandma Zarko always prepared was by design, tradition, or coincidence, blindingly white. There was a codfish stew with white onions followed by a plate of mashed potatoes, white cabbage, and cauliflower, garnished with a slice of Swiss cheese, everything saturated with garlic, sopped up with white bread, and washed down with your choice of white wine or white apple juice. The meal was served on white soap-box china on a white linen table cloth. We tidied our lips with white cloth napkins. For dessert, fried dough in various forms represented color for the evening, as it was a shade towards ivory, but just to make sure it didn’t offend the overall scheme, it was dusted with powdered sugar.

Then everyone would go to Aunt Marian and Uncle Bill’s to open presents, drink wassail and egg nog, and marvel at the decorations. Except when I was five.

Now most kids have only two sets of grandparents. I was lucky. I had three. There was my widowed Grandma Zarko, my mother’s parents, Grandma and Grandpa Lopin, and Aunt Marian’s parents, Jess and Mattie Lucas, who I got to call Grandma and Grandpa Lucas, even though they’re were not blood relatives, and strictly speaking, not even related by marriage. But you cannot have too many grandparents, and I was a kid and couldn’t have cared less about strictly speaking.

It was decided in adult pre-Christmas convocation, that if they were to pre-empt my asking what happens when Santa Claus dies, they had better do it when I was four. They had decided that I might be too clever to sustain a belief in the Old Elf until I was six or seven. So it was that Santa Himself appeared in our living room that Christmas Eve in 1953, and in front of the whole family, too, and not just to score a plate of cookies while everyone was asleep, but to hand me my own Santa-made (and totally forgotten) present. Well, almost the whole family was there. Grandpa Lucas missed it completely! But I told him all about it when he got back.

One night, a year and a half later, I lay in bed wondering, and finally called to my mother to ask the burning question; what happens when Santa Claus dies? Does somebody elect a new one? Sort of like the Pope? My mother gently revealed the truth. I found it not at all calamitous. But I did have one question. If Santa Claus is made-up, who was it came to visit Christmas before last? She told me.

“Oh!” said I, “I wondered how come he was wearing a mask…”

“If you asked, I was going to say; it’s cold in the North Pole.”

“…and why he had Grandpa Lucas’s watch on!”

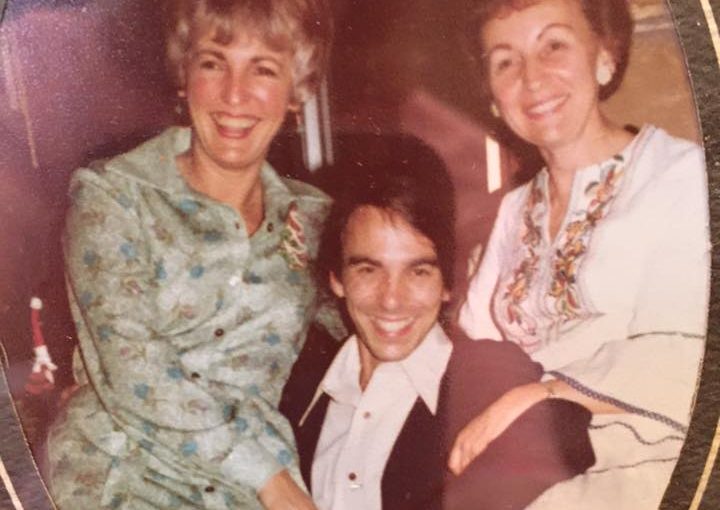

Photo: Linda, me, and Shirley — cousins.