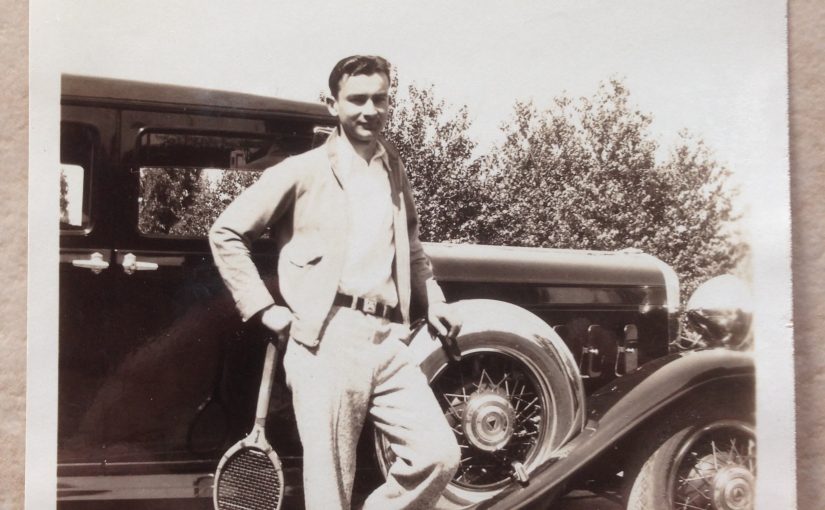

In response to a proposal on Facebook to share photos of our fathers, I found one I love. A twenty-five year old Pete Zarko is leaning on his tennis racket, posed with one foot up on the running board of what I believe to be his Hudson motorcar. Whatever it was, it was a classy vehicle, a luxury sedan, probably fitted out with some pretty nice accessories, too. Not a bad purchase for a young man starting out as an auto mechanic who, with his brother, tended the family orchards on weekends. The photo is dated – accurately I’m sure, by my mother whose archival talents were considerable – 1933, the depths of the Great Depression.

How’d you do it, Dad?

Let me be clear, I do not with that question mean to cast aspersions. My father was as honest as they came. If he discovered a 12-cent error on a customer’s bill, and the bill had already been paid, he’d spend ten cents reimbursing the overcharge. That was honorable, it’s what you did in business. Furthermore, the casting of aspersion has become sickeningly popular of late, and I tend to buck trends rather than follow them. So, nothing implied.

I’m just saying. Serious question. How’d you do it?

Once in his thirties, the tennis racket was put in a closet (and later in a basement), and the Hudson was replaced by a Ford pickup. The fancy clothes I never saw, they went away somewhere well before I was born. For a short period in the late fifties, I think, he and his brother bought a 30’s era Hudson (a beautiful thing, cream-colored with a tan canvas top) that they relished for awhile and sold for a profit. But during my childhood he left me with the distinct impression that he was embarrassed by the stylish tendencies exhibited in his youth. He had one sports coat, a herring bone tweed, that he wore for special occasions for the entire time I knew him.

When I was seventeen, I wondered furiously what happened to the camel hair top coat and the cashmere sweaters. I was way too skinny to have made good use of them, but cool was cool, and I would have loved to try them on, regardless of how baggy they might have been. The bowler hat I discovered in the basement, still in its oval box, and would take it out from time to time and wonder at its stiffness and generous size.

Some photos show my father with a pipe, another accessory I never witnessed his use of. I do, however, have a vivid memory of him saying in the car one night – provoked by what, I do not recall – that if any child of his were to become a smoker, he would beat the living daylights out of such child and for his own good, too. I was an only child, so I got that message loud and clear. Those words, by the way, so singular in their violence, were as close to a beating as he ever administered. As for the tobacco habit, my cousin, Pero, in Croatia was quite a smoker, and to be polite, I accepted cigarettes from him. I pretended to puff, and managed to drop them into whatever body of water was close to hand after a minute or so. I’ve never understood the appeal of nicotine.

How my father managed to have such style in the era of block-long lines for soup kitchens, aside from his being in California, may have been that he was always scrupulous with money. Once established with house and business, he placed paying his debts ahead of taking vacations or buying a popular new appliance. I agitated for the travel, my mother for the blender. Since Mom kept the books, the blender eventually fell into budget. Road trips were more complicated, but my travel urge was oft rewarded by careful research as to what favored destinations boasted antique autos.

Vintage and antique cars got us to Hearst Castle, to Harrah’s collections in Reno, to various spots in the Gold Country where unusual vehicles could be found, and to state parks and beaches to frolic with collectors who gathered to show off their prizes. I loved those cars, too; the majestic, the absurd, the odd, the extravagant. The Simplex-Crane built in the shape of a boat by a shipping magnate in San Francisco (the names alone were enough to warrant fascination – International Autobuggy, Hispano-Suiza, Mighty Michigan). The Stanley Steamer that used a specially heated splash-pan to build up a head of steam on demand, the deficit of steam cars being the long wait before you could go anywhere. The embroidered electric cars with drivers’ seats that could be reversed to facilitate conversation with rear-seated passengers (presumably once parked). The perfect Tucker that broke so much automotive ground that the big car companies felt compelled to litigate it out of existence, which once done allowed them to steal all the best patents.

My father owned seven or eight antique cars in various states of decrepitude, and two antique motorcycles. But he couldn’t say no to his buddies. He restored several of their cars during his retirement, but only finished one of his own. That was the Hispano-Suiza, which once complete was a beauty. It turned out, however, that the original body had been substituted by one from a contemporaneous Cadillac, and that severely reduced its value. He sold it to a doctor in South Dakota who drove it all around the country, despite a gas tank that emptied into its straight six engine with alarming speed.

I’d give anything to have a photo of Dad in his well-greased overalls, foot up on the Hispano’s running board, no tennis racket. Just for symmetry.