The first play I wrote was entitled “The Witch of Belon” and was a Halloween spectacular. I was eight. I either cajoled or guilt-tripped my mother to take it by dictation on her Royal portable typewriter, or a handwritten script was deemed to be unprofessional. However it was that August evenings were spent on the front porch as I acted out my masterpiece, rewrote, and corrected, my mother typing away at top speed and insisting that I stop talking when a new page needed to be wound into the patten, we spent a couple of weeks doing it.

The year before that, I announced at some point in September that I wanted to stage a play in our garage for Halloween. That spring my mother had taken me and my Aunt Mary to a production of Oklahoma! at San Jose State Teachers’ College, and it made quite an impression on me. I can distinctly remember climbing the steps to the theatre door with a six-year-old’s sensation of going to meet my destiny. I recall scenery, light cues, costumes, choreography, individual performances, and the surrey (with fringe on the top) they brought out for curtain call. All those elements were familiar to me, even though I had names for none of them. So, a few months later I decided to enter show biz. By Halloween I would be seven, and with that came responsibilities.

My mother suggested we go to the Sunnyvale library and inquire about children’s plays.

“Has to have a Halloween theme.”

“Why Halloween?”

“Because that’s when we’ll put it on.”

“What about trick or treat?”

“Before. Soon as it turns dark, we’ll do the play – so we can do lighting – then everybody can go trick or treat. It’s dark early by the end of October, isn’t it?”

She explained to the librarian what it was we were looking for, and amazingly she had an entire volume of children’s plays for Halloween. They were sensibly written to be narrative mime shows, so the burden of verbal delivery would be carried by an adult reading text, or at the very least, an older child. I was skeptical, but my mother looked so relieved and the librarian was so pleased at having addressed our need so sublimely that I kept my reservations to myself.

We had a two-car garage with sliding doors. This is an insignificant detail at this point in the story, but remember it.

I cast the six or eight roles from among my second grade classmates. My mother and another stage mother read the narrative parts, and the rest of us did our best to express the action physically. I’d rehearsed the other actors on the weekend prior. I remember nothing of the story except that I played a ghost costumed in too tight a sheet, and neither was I happy with my props. The performance garnered an enthusiastic response from our audience, and the curtain call – though it lacked anything so wonderful as a surrey – was thrillingly memorable.

So, as school let out on second grade and we settled into summer rhythms, my friends began to ask if there were going to be another play for third-grade Halloween. I pretended not to have given the idea any thought. In reality, I’d been imagining the next project to myself for weeks as I tried to fall asleep. So, in July I managed to manipulate a conversation with my mother into her asking what plans I had for Halloween.

“Well, I think instead of inviting just a few kids and their parents, we should invite the whole third grade.”

“And their families?”

“Of course.”

“That’s a lot of people. How will we fit them into half the garage?”

“We don’t have to. We’ll seat them in the driveway facing the garage.”

“On what?”

“We’ll borrow benches from catechism.”

“We will, will we?”

“Okay, I’ll ask. And we should have refreshments for before the show.”

“And where do we get those?”

“Somebody can organize the other mothers.”

“Somebody?”

“Not you! Like Bobby’s mom. She’s nice and I bet she’s good at that.”

“Okay, so we need a play…”

“Obviously.”

“We’ll go to the library next week and…”

“No, I didn’t like that play that much, and I read most of them in that book, and that was the best one, so, I’ve been thinking…”

And such was the road that led to evenings in August on the front porch while my mother typed and typed and I talked and talked. I cast the play as we worked. Connie was a natural comic, and I liked her a lot, so she would play the title role because someone with good comic ability would bring out more nuance in the character. And Jeff would play the prince because he was my best friend and had that sort of heroic bearing you’d expect from a prince.

I understood that the garage gave us a technical advantage if viewed from the driveway, that is both doors could be drawn to one side, and while one scene was being acted, a change of scenery for another could be happening on the closed half. Then stage hands would draw the doors to close the first scene and astonish the audience with a different location. I drew my inspiration from a visit to City of Paris department store in San Francisco where I experienced my first elevator. We went into a box, we said something to the nice lady in the corner, waited awhile, and when the doors opened someone had completely changed everything; furniture, goods for sale, people… it was amazing! Two or three years later I was going for the same effect with the family garage.

I don’t know how many years the Halloween plays continued, I do know there was a fourth grade play called something like “The Witch of Belon Returns”. After that, all I remember is playing the king in one of the later opuses and improvising liberally on my own script. From the bottom of my heart, I thank my parents for putting up with thirty-five classmates, their siblings and parents, most in costume, running through the yard and house, while I ordered kids around in auteur director fashion.

What perplexes me is why after college I chose to doubt that theatre was all I’d ever wanted to do. To paraphrase from The Music Man, I became a dewy young guy who keeps resisting all the while he keeps insisting.

“So, how do you think it went? Did the kids like it?”

“There are problems with act two. Would you consider helping me type the rewrites?”

The scripts are actually filed away somewhere, I discovered them among my mother’s things. I didn’t have the courage to read them.

Happy New Year Everyone!

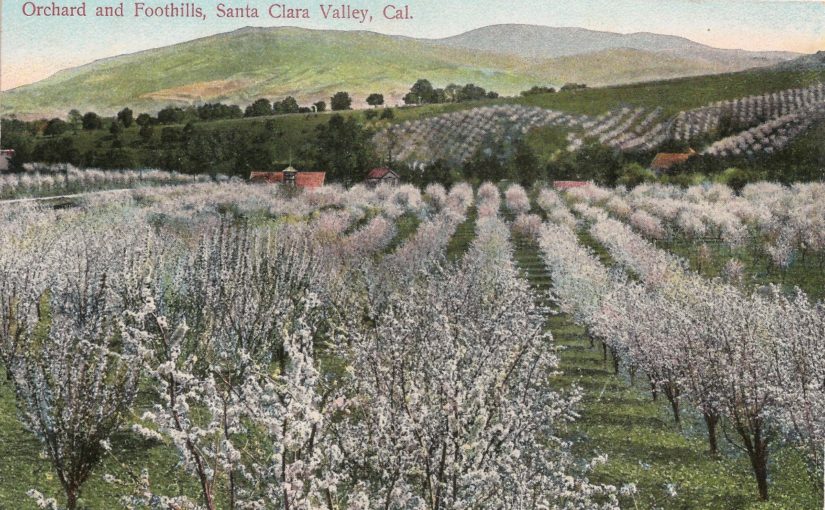

Photo: the surrey that I couldn’t work into the show.