Even though Grandpa and Grandma Lucas were not blood relatives, it was clear to me as a child how they fit into the family. They were my cousins’ actual grandparents on loan. How Aunt Alice and Uncle Bert figured into the family was more mysterious, and still is. They were perhaps Aunt and Uncle to my Aunt Marian, therefore Alice may have been Mattie Lucas’s sister. I’m really shooting in the dark, here. But I felt pretty much the same about them as the Lucas’s, you can never have too many uncles and aunts.

Bert and Alice lived on the same block as we did, only on the other side. We walked down South Mathilda to Olive Street, turned right, and their house was on the corner of Taaffe. (I say walked, but despite the tiny distance, we often drove.) I loved that house. It was a California Mission bungalow, all rough troweled plaster and terra cotta roof. You entered from a small porch into a living room and directly opposite a wide arch that presented the dining room which had windows along the opposite wall onto a patio and a walled garden filled with fuchsias. To the left of the dining room was Bert’s drafting studio; more windows, tiled floors, triangles, Koh-i-nor pens, sharpeners, scale rulers, and velum. It led into the patio. To the right of the dining room was a long, narrow kitchen. There was a fancy-painted breakfast nook. Alice’s stove was several shades of green enamel, and had control knobs that were somehow in the shape of a pendant. (Don’t ask me how, it’s a memory.) Through the kitchen you could go down a set of aromatic wooden stairs to the basement where the men would gather for billiards.

It was a magical house.

I don’t remember having spent an actual holiday with Bert and Alice. But for some span of years, the family celebrated Leftovers Friday, when we all gathered again to finish off what we were too stuffed to finish on Thanksgiving. It was better than being stuck with a refrigerator of whatever it was we had provided for the actual feast, like four Tupperware containers of mashed yams. It allowed us to continue to enjoy a varied table in each other’s company. At least a couple of these day-afters were held at Bert and Alice’s, and I remember them being more convivial than the holiday itself. Some of the adults were there on lunch hour — extended to allow for pumpkin pie — and were delighted with the break in routine. The style of service was decidedly tin-foil and wax paper, so everyone was more relaxed. If the white meat was a bit on the dry side, we all knew it already, no one had to point it out, and no one had to be embarrassed about it either.

One year when I was seven or eight, Bert had for reasons forgotten set up a public address system. The speakers were in the dining room, the microphone in the front bedroom. He said a few words of welcome, everyone laughed, and some of the curious went up to examine the source. I was not among the curious. It seems that I’d heard the voice, paid little attention to the words, and assumed someone had turned on the radio. I wanted Dad to take me downstairs for a game of eight ball.

It was usually on a Tuesday. Uncle Bill would show up unannounced, and tease my father into doing his day-end bookwork a bit later than usual so we could go over to Bert’s for pool. I don’t know how Dad spared the time. His billings could take more than an hour, he seldom got home before 7:00, and was in bed by 10:30. But two or three times a month he agreed to join his brother for billiards.

There was a rotating group of regulars, and my uncle could always scare up one of them to round the group out to a regulation four; he and my dad, Bert, and another guy from the neighborhood. They played the real thing, billiards with two white balls and a red, cushion shots, elegant set ups, arcane terminology. There were pictures on the walls of dogs playing poker, of sylphs standing prettily in a bosky glade, of an old woman and her butcher weighing a chicken, both disrupting the scale. The men swore. My father almost always won. His background as a machinist fit nicely into the precision of the game.

After a few rounds with his friends, or if a second neighbor showed up to crowd him out, he’d come over to the pocket billiards table, colloquially known as pool, and combination play and teach me through one of several games. These were good tables – slate beds, oak gutters, thickly felted cushions. The balls made a wonderfully satisfying rumble as they returned from their pockets to the rack at table’s end.

That’s where I wanted to go while we waited for leftovers to be heated and served. But Dad enticed me to take a look at the microphone in the front bedroom. Bert followed. It was a splendid thing, this microphone; chrome and shining, hefty and complex. Bert turned on the amp and tested the mic with a tap.

“Say something.”

I was too shy.

“Try it. Have you never used a microphone before?”

“No,” I mumbled into my sweater.

“Well, I’ll leave it on in case you get the urge.”

I followed them back to the dining room. Not a word was uttered about pool or the basement. A few minutes later I gave in to the call of fate and retraced my steps.

“Hello.” My voice boomed back at me from twenty feet away in a most satisfactory manner. “Hello to everyone in the dining room.” That got a laugh. This felt dangerous. “And welcome to Leftover Thanksgiving hosted today by our favorite aunt and uncle, Alice and Bert! Let’s hear a round of applause!” They clapped. My future as a striving theatre professional was sealed in that moment.

I have been justly accused of extending pre-show curtain speeches past the useful limit while functioning as artistic director at one theatre or the other; an indulgence with roots in that microphone. I couldn’t stop talking. I listed names of family and their imagined responsibilities for the day. I reviewed the dishes on order, complimented the cooks, anticipated who would have to leave early, who would get stuck with the dishes, who would get to take home the leftover, leftover stuffing.

After several minutes of my imagining a happily amused audience, rapt at my wit and sophistication, my father crept in.

“Just going to adjust the volume, here,” he said, masking the amp with his body.

“Not loud enough?”

“Something like that.”

He returned to the table, I kept right on going. Uncle Bill had to interrupt to let me know that I was missing the turkey. I imagined glowing faces and an enthusiastic welcome, the way you saw an audience greet its adored master of ceremonies on television.

There was none of that. Everyone was eating, laughing, talking. My cousin Shirley patted the chair next to her. My plate was already filled.

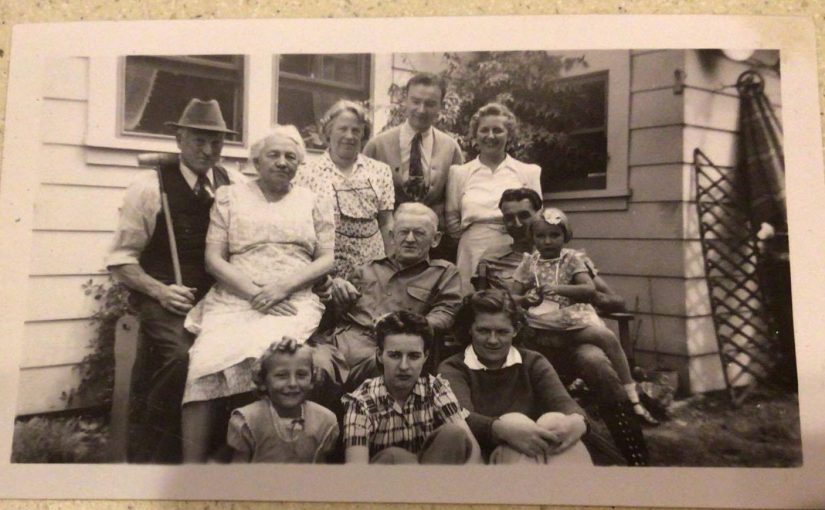

Photo: Bert is seated center, Alice is standing behind him.