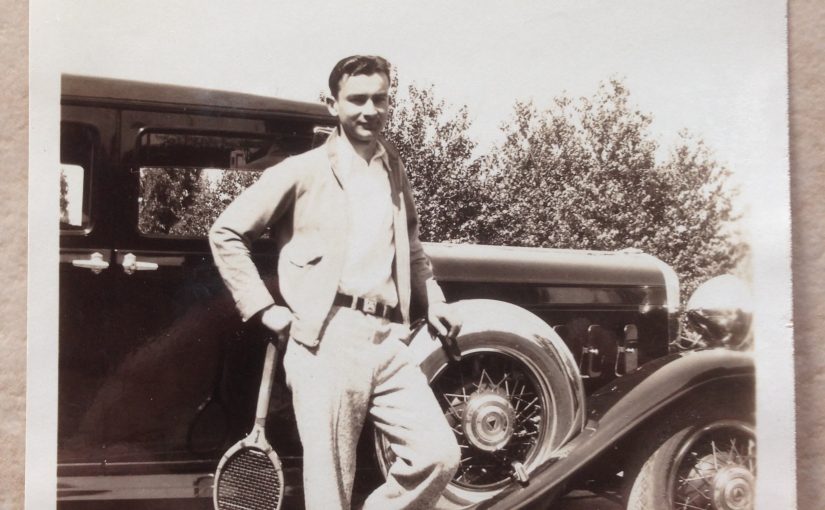

A twenty-five year old Pete Zarko leans on a tennis racket, one foot on the running board of his Hudson motorcar. It was a classy vehicle, a luxury sedan, fitted out with all the best accessories. Not a bad purchase for a young man starting out as an auto mechanic who, with his brother, tended the family orchards on weekends. The photo is dated – accurately I’m sure, by my mother whose archival talents were considerable – 1933, two years before they married and during the depths of the Great Depression.

How’d you do it, Dad?

I do not mean to cast aspersions. My father was as honest as they come. If he discovered a 8-cent error on a customer’s bill, and the bill had already been paid, he’d spend ten cents reimbursing the overcharge. That’s the honorable thing. It’s what you do in business. Besides, the casting of aspersions has become sickeningly popular, and I tend to buck trends rather than follow them. So, nothing implied.

I’m just saying. Serious question. How did you do it?

Once he was in his thirties, the tennis racket was put into a closet (and later, a basement). The Hudson was replaced by a Ford pickup he bought for above market from a Japanese-American customer who was being sent to an internment camp. The fancy clothes I never saw. They went away somewhere well before I was born. For a brief period in the early sixties, he and his brother Tony bought a 30’s era Hudson (a beautiful thing, cream-colored with a tan canvas top) that they enjoyed for awhile then sold for a profit. But during my childhood Dad left the distinct impression that he was embarrassed by the stylish indulgences of his youth. He kept one sports coat, a herring bone tweed, that he wore for dressing up the entire time I knew him.

When I was seventeen, and beginning to wake up to the possibility of fashion, I wondered furiously what happened to the camel hair top coat and the cashmere sweaters other photos showed him wearing. I was way too skinny to have made any use of them, but cool is cool, and I would have loved to have at least tried them on. His bowler hat I discovered in the basement. It was still in its oval box. I would take out from time to time to ponder its stiffness and generous size.

How my father managed to buy such fine clothes in an era of block-long lines for soup kitchens — aside from his living in a farming community in northern California — may have been due in part to his scrupulous attitude towards money. He wasn’t afraid to spend on whatever he considered worth the cost, but he placed paying his debts ahead of taking vacations or buying a popular new appliance. I agitated for the travel, my mother for the blender. Since Mom kept the books, the blender eventually fell into budget. Road trips were more complicated, but my travel urge was sometimes satisfied by careful research as to which favored destinations boasted antique autos.

Vintage and antique cars got us to Hearst Castle, to Harrah’s collections in Reno, to various spots in the Gold Country where unusual vehicles could be found, and to state parks and beaches to frolic with collectors who gathered to show off their prizes. I loved those cars, too; the majestic, the absurd, the odd, the extravagant. The names alone were enough to warrant fascination – International Autobuggy, Hispano-Suiza, Mighty Michigan. The Simplex-Crane built in the shape of a boat by a shipping magnate in San Francisco. The Stanley Steamer that used a specially heated splash-pan to build up a head of steam on demand — the deficit of steam cars being the long wait before you could go anywhere. The embroidered electric cars with drivers’ seats that could be reversed to facilitate conversation with rear-seated passengers (presumably while parked). The perfect Tucker that broke so much automotive ground the big car companies felt compelled to litigate it out of existence, which once done allowed them to steal all the best patents.

My father owned seven antique cars in various states of decrepitude, and two antique motorcycles. His goal was to restore them all, but he couldn’t say no to his buddies. He restored several of their cars during his retirement, but only finished three of his own. Those were a Model T Ford, a Grant roadster, and a 1923 Hispano-Suiza. The Hispano was a real beauty. It turned out, however, that the original body had been substituted by one from a contemporaneous Cadillac, and that severely reduced its value. He sold it to a doctor in South Dakota who drove it all around the country, despite a gas tank that emptied into its straight six engine with alarming speed.

Some photos show my father with a pipe, another accessory I never witnessed his use of. I do, however, remember him saying in the car one night – provoked by what, I don’t recall – that if any child of his was ever caught smoking, he would beat the living daylights out of him, and for his own good, too. I was an only child, so I got that message loud and clear. Those words were as close to physical punishment as he ever came to giving. As for me and tobacco, my Croatian cousin, Pero, was a smoker, and to be polite, I would accept a cigarette from him from time to time. I pretended to puff, and after a minute or two dropped it into whatever body of water was close to hand. I’ve never understood the appeal of nicotine.

And when style is betrayed by truth, Dad’s pipe and Hudson sedan may have just been photographic props. Even the camel hair and cashmere may have been on loan. In fact, I have vague memories of that being the case, but there is no one left alive to ask. The racket and tennis whites are real, however. Because he loved playing tennis in his twenties, he convinced me to take it for physical ed in my first year of college. It was the only class I ever flunked.

I’d give anything to have a photo of Dad in his well-greased overalls, foot up on the pickup’s running board, no tennis racket. Just for symmetry.