My father built his own auto repair shop shortly after the war. It was quite a grand structure with an impressively engineered single barrel vault made of timber, and with room enough for six active repair bays. In front was an office, but as my mother performed official tasks and preferred to work at home, it was never used. Instead they rented it to Fred Brackenbury who repaired radios, then a bit later, televisions. Brackenbury had a sign painted over his entrance. Dad never painted a sign, but by the time I was about six, I was pretty convinced that he was waiting to put one up that said “Zarko and Son”.

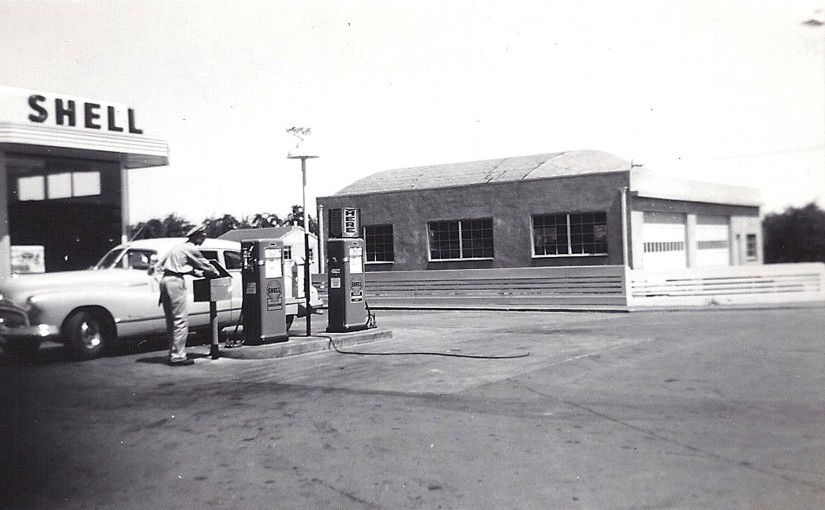

My parents bought the lot on the corner of Mathilda Avenue and El Camino Real in 1945. There was a house on it, built in 1925, and a large garden, probably a few fruit trees. They moved the house a half block away not long after they bought it to free up the property for commercial use. My mother rode inside the breakfast room during the move, because as she said, “When else will I have the chance to ride a house?” She tried to get Dad to join her, but he thought that would be silly.

My father loved mechanics like I loved theatre. In about 1920, when they were in their teens, he and his brother, Tony (aka Bill) created a functioning motor vehicle out of discarded farm equipment. His first job was as a cleaner at Redwine Ford dealership in Mountain View. Maybe he didn’t get his hands greasy pushing a broom, but at least he would be in the company of those who did.

By the end of the decade, he had gone into business with a man named Frazier, when they opened a Ford dealership on Sunnyvale’s main street. Not bad for a farmer’s son. I’m sure that Frazier had a first name, but even though he was oft-mentioned in our household, I don’t remember ever hearing it. Willard! Okay, but for home use he was always called Fraizer.

I suspect that for Fraizer & Zarko, a combination dealership and repair shop, a degree of order and cleanliness was enforced that was absent in Pete Zarko’s Garage. Once on his own, Dad could revel in grease, and he did. I loved it, too. All that caked, black goo. He’d put me to work scraping pans of some vague automotive purpose, and it was so satisfying to feel the thick resistance of a heavy layer of coagulated oil give way to the tool’s stout blade. Waste oil, and I believe even the goo, was stored in large cans and picked up weekly to be recycled. Oil was the gold of his enterprise, and he treated it with respect. He also threw the stuff that was too filled with particulate matter to be cleaned onto the ground behind the shop so he wouldn’t be bothered with weeds. I’m sure that when the City transformed the corner into a park, they had some serious environmental cleanup to do.

I was about eight when Dad first invited me to work with him on the family Ford when it needed more than windows washed. We started with simple things like cleaning spark plugs and distributors. By the time I turned ten, he had taught me how to adjust timing, clean carburetors, change oil, and top off brake fluid. By the time I was twelve I was under the car with him when the clutch needed changing, brake drums needed adjusting, and other gloriously greasy work needed doing that I remember the fun of, but not the purpose.

Still, I knew in my gut that the sign Dad wanted to paint wasn’t going to happen. I enjoyed peering into engines and rolling around under cars, and when he gave me clean up jobs, I did my best to exceed expectations (and tried to hide my disappointment at how quickly everything got messy). And I admired the garage, loved my father, and was proud of his good reputation. But I didn’t relish mechanics. Didn’t even really like riding in a car all that much, let alone fixing one. I preferred to walk.

I started taking walks as soon as it was physically possible. I vividly remember exiting Grandma Zarko’s yard on the Waverly Street side, pushing open the white gate, and heading for parts unknown. A bemused neighbor asked where I was off to.

“I’m taking a walk,” I proclaimed. And I passed three houses before my mother discovered I was gone and came running after me.

I walked to and from school in first grade. My grandmother’s house was a short distance from Adair Elementary, so it began with lunches, but quickly advanced blocks long treks.

I remember hiking home one day – it had to have been first or second grade, because Mom was still driving the 1936 Ford Victoria – about to cross Iowa Street, when she pulled up, rolled down her window, and with a radiant smile offered me a ride.

“No! Can’t you see I’m walking!?” And I truculently crossed Iowa and stomped the few blocks home.

My love of walking is in my DNA, I guess. The same way that love of a humming engine was in Dad’s.

So, here we are, I’m maybe seventeen, and we’re giving the car a tune up. I am perhaps not pretending enthusiasm as strongly as I may have done a few years prior. I had been strongly lured by a theatrical siren, and grease was losing its charm. I harbored hopes that something besides my saying it out loud would convince my father that I was not meant to follow in his footsteps.

We drain the oil pan. I take the used oil to a recycling barrel. Dad hands me the five-quart oil can to be filled from the new-oil barrel across the shop next to the restroom. I go. I fill it. The oil is transferred to the Ford engine.

“Let’s top this sucker off just a little, I think it wants another half pint.” That’s his polite way of saying that I’d not filled the can. I sulk back to the new-oil barrel.

“Oh, my god! Oh, my god! Oh, my god!”

That’s me. My Dad never gets excited like that. However, this one time he joins me at trot.

I’ve left the tap open. There’s now several gallons of liquid gold covering the floor from parts shelves to grease rack. Totally without fuss, Dad picks up two sheets of tin, inserts a funnel with a filter into the barrel, and uttering not a word of fault or blame, we scoop as much oil as we can manage. The rest we sop up with a layer of sawdust, and sweep into a trash can.

I could see the sign saying Zarko and Son falling into an imaginary heap. It wasn’t a sin, what I’d just done, but it sure as heck was a signal, and Dad read it as clearly as I had hoped he would.

We still spent many hours leaning over fenders and scooting under transmissions, but now we did it because… well, that’s what we did together. When Dad retired early so he could restore his antique autos, he leased the business to his longtime employee, Louie, and no sign of any kind was ever painted for Zarko’s Garage. When Louie retired, the City bought the land from my father, and for a brief period before the garage was turned into a bank, I imagined what an interesting theatre it would make.

Then the City tore it down and planted trees.