I woke at about 2:00 am with a terrible stomach ache. I lay in bed for awhile calculating what time it must be on the East Coast. Polls in New York closing about now. I took an antacid. No effect. Finally, I got up at about quarter to three, may as well check Facebook, news sites, see what’s going on. Nothing yet. Too early. Took Maalox, that helped, went back to bed.

Had a dream that Hillary won. Not a huge win like I was imagining might happen, just a gentle one, celebrated deftly and with humility as would be the delivery of a beautiful cappuccino first thing in the morning at your favorite bar. I’m not embroidering, here, that was the dream.

I awoke again at 6:30 and the news, as we all know, was quite different.

More than anything, I wanted to be out in my lovely Orvieto. The people here balance me. Friend Roy posted on Facebook. He was at Capitano del Popolo, I posted back, stay! I’ll be there in a minute.

He sat, pinked-eyed, said he’d been on the verge of tears all morning. My reaction was more of the numb and tight-throated type. Perhaps resisting tears, I don’t know. I’m not always in touch with where my emotions want to take me. We sat, sipped, wondered, hoped, despaired, and metaphorically scratched our heads. Roy is one of the best conversationalists I’ve ever met, yet it was difficult sometimes to continue. Words don’t always serve. But this morning the connection with someone who spoke my mother tongue was my first need, and Roy is so honest and true.

Back in the piazza, we were joined by a couple of other distraught Americans. I excused myself, and went on to the farmacia. The tight throat was partly emotional, partly because I’ve been experiencing a lot of stubborn mucous, so I asked the nice lady there (one of them, anyway) for a remedy.

I asked how she was feeling. “Okay. Not so good. I dunno.” Yeah. It’s a tough day. “The election?” Yep. “I’m devastated, disappointed, astonished, have no words.” I heard senza parole in both languages quite regularly this morning. But finding the words is somehow important. They create realities, and in the midst of the unreal, discovering them again helps us regain a balance. “And I have to speak carefully, because I am afraid.”

I left for Blue Bar. Antonio, the waiter at Ristorante Il Cocco was out front cleaning the storm drain. I have said hello and admired this young man for years. He works at whatever is in front of him with the concentration of an artist, always, and with joyful absorption. We’d not met or been introduced, but nonetheless have always waved and smiled whenever we passed. Last spring, on my last day here, he walked up and shook my hand. “We should know one another’s names.” We don’t know much more than that these six months later, but an exchange with him is always valued.

“How are you?” So, so. “Yeah, but the weather seems…” No, not the weather. “Oh! Yeah. I know. Affected me the same way. I’d started to forget about the U. S. election, it seemed a foregone conclusion, then suddenly, Trump. I have no words,” and he proceeded, as we all have done, to try to find some anyway. “This is a great danger to the world. But we can’t stop working, can we?” We shook hands again. That picked me up a notch.

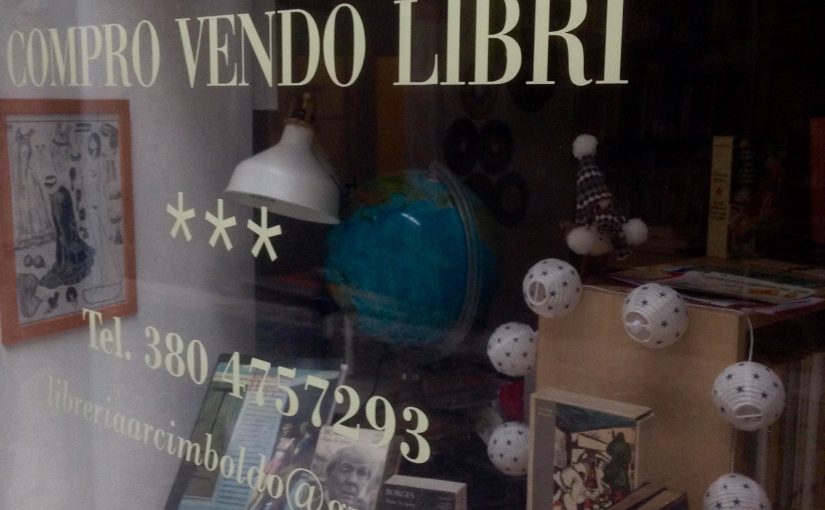

Blue Bar was my destination. Antonny would be an oddly steadying influence in his highly animated fashion. The counter was strewn with dishes and cups. The performer, the clown, the affectionate teddy bear that Antonny is, was fully engaged. “Everyone in here because of Trump! Very busy, all a mess.” He was flying, but not because he was happy about the election. “World War Three” he said while making his lower jaw tremble, his favorite expression of fear and sadness. “I have no words.”

Keagan was at the bar. He’s the son of an American mother (who lives nearby) was born in the U. S., but raised here. His English is exceptional. “I have no words, either. My mother can’t believe it. It’s a dangerous development, also for us.” It seems to me that the next few weeks are going to be tumultuous. “In Italian we say, chi vivrà, vedrà. Whoever’s alive will find out.” Antonny enthused that they have the same expression in France. “In America?”

Had I been able to formulate a response, it may have been this: “In the two-hundred fifty or so years since the birth of the Republic, Italy and France have been through numerous political and cultural upheavals, have survived wars and catastrophes of every kind. Perhaps, the U. S. just hasn’t needed that expression yet. But somehow, a lot of Americans have come to fear that things are dire enough that we do. And maybe will.” But there were no words.

The phrase touches on the existential core of why I feel as I do, today. The events of the last few hours are a reminder that we all have to give up the story at some point, pass it on to others. I can imagine a dozen horrible outcomes from this day, ones that will haunt the planet for decades. I can imagine that all my work is worthless. It is that imagining, and the fears it engenders, that has brought us to this point, and we mustn’t indulge in that imagining, no matter who we are, any further. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy and fails to make the story we pass on more interesting.

A friend’s wife who is suffering dementia was in the next room with her caregiver. She smiled as I came in. I half envied her at that moment. As I left, she smiled again, and we spoke Italian to one another, how glad we were to see each other, that kind of thing. “Give me a kiss.” I’d love to. And a hug? “And a hug.” I kissed her on the cheek and hugged her. Still smiling, “That was a nice kiss.”

I returned my dishes to the counter – American behavior, comporatmento americano, they call it here. My friend’s wife turned to Antonny and asked him for a kiss. He was immediately forthcoming with both kiss and hug. He returned to the counter. I told him that she had asked me for a kiss, too. “We are rivals, then! She cannot love us both! This is very serious, Mr. Zarko.” He winked, threw a saucer up his back and caught it over his shoulder, then pulled a coffee.