My language teacher, Mariella, shared an fascinating linguistic fact with me the other day. All pharmaceuticals here are dispensed in blister packs. Tucked into the box with them is a rather large, oft-folded piece of very thin paper upon which is printed in very small type, instructions, directives, disclaimers, warnings, and other such having to do with the medication packaged therein.

These pieces of paper are called “bugiardini,” which translated literally means “little lies.”

What follows are a kind of bugiardini, warnings and disclaimers from a cappuccino-fueled imagination.

Particular Use of the Imperative Form of Verbs

When using the imperative form (do this, do that) with pronouns, a number of elaborate rules kick in, rules that can become increasingly complex depending on who is being addressed.

For example, when addressing a woman with dark hair who is the daughter or wife of a Senator – or the sister of a fisherman from Calabria – one uses an imperative form of the verb identical to the future anterior form, but which is in fact the “personal imperative very particular” (imperativo personale molto particolare) not the future anterior, even though it behaves exactly as if it were. If, however, the woman in question is the sister of a Senator, the indicative second person, familiar or formal, is used. Moreover, if she is both the wife of a Senator and the sister of a Calabrese fisherman, a form resembling the third person of the present subjunctive mood is employed. Like all Italian grammar these usages are elegant and perfectly sensible once you truly understand.

A further refinement to the rule: if the woman, regardless of hair color or male relations, is your mother, you don’t use the imperative at all. You ask nicely.

Progressive Ultra-Nationalists and Grammar Reform

As we’re on the subject of grammar, members of Italy’s Progressive Ultra-Nationalist Federation (FUNP) while observing the political “climate” of the U.S. have perceived an opening for Italian to supersede English in international commerce and science. American English, as they see it, is degrading so rapidly that within months (and possibly weeks) it will be all but useless save for hurling insults, throwing tantrums, and lying. In response, FUNP has launched a program to streamline Italian grammar, called The New Italian, thus rendering their language more agreeable to non-native speakers, and improving the chances of its replacing the form of gibberish English is quickly becoming.

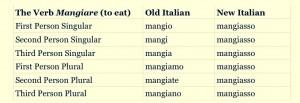

An example: “posso” means “I can” or “I am able.” Because that is precisely the spirit FUNP wishes to associate with The New Italian, all verb forms will be based on posso, as illustrated in the FUNP’s table below:

Critics of the plan say implementing such change will effectively dumb the language down to a level almost equal with that of contemporary English. Proponents counter that dumb is the wave of the future, and as Italy needs to beat other countries to the punch, it’s now or never. The debate rages.

To help us stay on top of this story’s developments, Fox News will air a series called “Why Language is the Problem; An Unbiased Report.” MSNBC has similar plans with its show “Americans Who Hate English.” CBS is weighing profitability before it commits to a three-part exposé “Degraded Discourse – Necessary for a Healthy Economy.” Stay tuned.

Cross Town Traffic

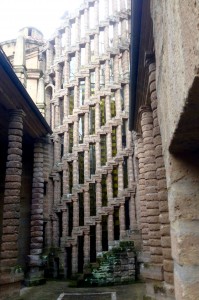

Roberto Mosecci, an expert on civic planning and economic development with offices in Milan and Los Angeles, proposes a radical rethinking of how Italian hill towns are accessed by tourists and delivery vehicles. Having chosen Orvieto for his pilot program, he instantly identified the city’s distance from the autostrada as the principal reason for its failure to patch plaster and freshen paint. “One has to ride an antiquated form of transport (the funicular) to reach the town at all, and once there, the streets are narrow and impractical, these together discourage introduction of chain stores and other essential amenities, including importation of fresh building supplies.”

Mosecci’s proposal will send the Autostrada del Sole directly through the center of town. The funicular (which he hates “with a passion as deep as hell”) will be replaced by a newly-excavated automotive diverter. Four lanes of bi-directional traffic will plunge through the current Piazza Cahen, follow the route now taken by Corso Cavour (straightening the old-fashioned jogs and curves) turn Piazza della Repubblica into an Area Servizio with a Starbucks, MacDonald’s, and Pizza Hut (thereby introducing convenient and profitable food to the city’s core) down Via della Cava, and out through a widened, heightened, and completely restructured, Porta Maggiore, capped by a revolving Renaissance-themed restaurant.

“The Etruscans would approve.” he says confidently. “When they built Porta Maggiore, it was modern in every sense of the word – to them. We aren’t “them” anymore, so are compelled to honor the founders’ vision by bringing it up to current commercial standards.”

In his White Paper on Urban Renewal he lists the many benefits that will accrue: the razing of architecturally out-of-date buildings, a direct cutoff to subterranean parking covered by a much-needed green space to replace Piazza del Duomo, and improved efficiency of access to major tourist locations, such as the two or three churches not tagged for conversion into high-end health spas, a brand new steel-framed minimalist/brutalist version of Torre del Moro, and the city’s only Chinese restaurant.

“A crosstown highway will bring Orvieto, and other hopelessly inefficient hill towns, into the twentieth century,” he concludes. When asked about the twenty-first century, Mosecci responds “I am a preservationist; decades-old representative global traditions must be saved before it’s too late.”

Medieval World Italia!

In an unpublicized move, Sidney Corp, by special arrangement with Commune d’Orvieto, has purchased first rights of ownership to the city’s exposed external surfaces, and title to all revenue-producing activities, with an eye towards creating a theme park out of the city and its environs under the banner, Medieval World Italia!

“Let’s face it,” says Sidney Corp spokesperson Dyslexia Proze, “the Dark Ages are ‘in’ with a vengeance. But people want both the genuine experience and the convenience of facilities they’re accustomed to. We at Sidney Corp are going to give them what they want.”

The first phase of the entertainment giant’s feasibility study involves the overall “look and feel” of the town. “The cliffs surrounding this cute little burg are charming, in their way, but the color is depressing. All that gray and brown. So, we’ve begun a systematic study to scientifically determine alternate coloration,” she explains, pointing to a number of paint samples already in place around the city. “Before anything, today’s tourist wants an easy-to-absorb and primarily visual experience that photographs well by providing excellent contrast with the posed subject or selfie,” she explains.

Thus, Sidney Corp is testing two colors at a time, currently white (seen as most likely to attract wealthy Americans) and red (for who else? The Chinese.)

“We’ll make a decision based on data collected by remote sensors placed along the so-called Anello della Rupe (to be renamed Cliff Land within the new park) to measure sweat, pulse, panic response, and urge to pee when confronted by the color swatches, then we’ll match that data to national averages. We expect results within a year. Our current projection, founded on demographic surveys of Australian passengers deplaning at Fiumacino airport, is to paint the entire cliff area one solid color with a contrasting hue for the town. The Duomo (renamed Holy Land, pending conclusive marketing surveys) and quaint atmospheric detail elsewhere will be analyzed by computers to determine which parts to leave exposed so as to enhance the Dark Ages ambience park-goers flock to. Then, to give it that real flavor of authenticity, everything will be draped in sackcloth.”

Fun features of the plan include: a “sudden drop ride” off Torre del Moro, a haunted castle mechanized tour of Palazzo del Popolo, and a “living maze” disorientation experience (terrifying but safe) in the ex-medieval quarter (to be re-dubbed Inquisition Land.)

“While we respect history for its commercial value,” explains Ms. Proze, “we don’t feel in any way obliged to perpetuate it.” She followed her remarks with a cryptic, if somewhat disturbing, wink.

New Sanitary Ordinance

Italian culture prides itself, and rightfully so, on its elegant sense of design. When applied to laws, regulations, and ordinances, the culture’s appreciation for nuance and equilibrium reaches a dizzying degree of refinement.

In a recent move on the regional level, officials in Perugia have announced new laws regarding sanitary practices. They stipulate that all viral or bacterial disease in Umbria first be contracted, improvisationally, by American males living in towns founded by Etruscans and who are at least sixty years of age, of ancestral heritage not Italian, and are otherwise healthy. As with all things in Italy, the micro-organisms in question have fallen immediately into line under the recently passed regulations, and are working hard to assure compliance.

I am proud to support my adopted (possibly part-time) country in this worthy endeavor.

Viva Italia!