My dear friend Erika, an American who married Italian and has been living in Orvieto since 1958, lately observed that Christmas gifts are bulky and hard to carry while juggling a cane and a dog. This year, she would give memories. Memories grow more abundant with every passing week, and as I am now of the generation that lives on the far fringes of its living memories, there are plenty of gifts to go around.

When it was my grandparents who represented the farthest reaches of living memory, they recalled high-button shoes and handlebar mustaches. My generation reaches back to colorfully striped bell-bottom trousers and, well — handlebar mustaches. There is a circularity in play regarding youth fashion.

Before they fade, I’m wrapping the memories that are still crisp and giving them forth as offerings for the winter holidays. The specific holiday is not, to me, all that important, so only some of the memories will be holiday related. That we gathered to celebrate our family in our family’s way is what ties me to these recollections, and, I hope, will stir reflective memories of your family’s way, in turn.

Let’s begin with Christmas, specifically my fifth Christmas Eve. I was the youngest among us, so it was deemed that I should be the one to personally meet Santa Claus.

Being only four, I didn’t have a lot to draw on as to what was or was not traditional, but the family gathered at my parents’ house that year – 1953 – the only time I can bring to mind that we were not at Aunt Marian and Uncle Bill’s. Even with little knowledge of precedent, I remember being excited that we were hosting the festivities.

What I don’t recall, but would bet was traditionally observed, was the pre-gift giving meal at my grandmother Zarko’s. The ancestral estate was a seven-room farmhouse build in about 1908. It smelled of garlic year around, of quince candy during the winter months, and of Croatian strudel with apples and apricots in late fall. The Christmas Eve smell was boiled cod.

I don’t remember there ever being Christmas decorations or a tree, there was no room. There was a radio the size of a refrigerator, a pump organ that no one knew how to play, a glass-fronted hutch filled with china extracted from boxes of detergent. There were butter-block chairs and a matching settee upholstered in crackling black leather and stuffed with horsehair on top of spiky, creaky springs. The kitchen was dominated by a round oak pedestal table that my mother had found somewhere for five dollars, and which she brought home – my folks lived with my grandmother in those days – in the rumble seat of her Model A Ford. Warming the kitchen was a combination wood and gas burning stove with a special tank for hot water. The phone in the hall had a call button that you pushed to gain an operator’s attention so you could vocally tell her the number of the person you wanted to reach, or if you couldn’t remember the number, the name.

On a back porch that always felt like it was about to slide into the vegetable garden, was a squat, black cast-iron wood stove, the oven door graced by a white porcelain panel that showed the temperature with a black needle, and a little mica-glazed window. The other half of the porch was glassed-in and home to a perplexing array of coleus plants, spilling over their shelves and onto the floor. There was always a gallon tin of extra virgin olive oil sitting on an oil-saturated side table, a hole poked into its lid that was stopped up with a twig. As a kid I imagined the twig was, logically, from an olive tree — but probably not.

Perhaps because they had lived there for so long, my parents always entered the house through the back porch. Everyone else used the front door, a narrow panel precariously placed at the top of four narrow steps that sported no handrail. The screen door opened out. For every festive occasion, lives were risked just to attend dinner.

And every Christmas Eve and Good Friday, Grandma Zarko cooked dried cod. And at every codfish dinner, my Uncle Bill would quip that to make the stuff eatable required dragging it behind a tractor for two hours, soaking it in acid, pounding it with a hammer, and boiling it overnight. He was exaggerating, but only slightly.

The meal Grandma Zarko always prepared was by design, tradition, or coincidence, blindingly white. There was the codfish stew with white onions followed by a plate of mashed potatoes, white cabbage, and cauliflower, garnished with a slice of Swiss cheese. Everything was saturated with garlic, sopped up with white bread, and washed down with your choice of white wine or white apple juice. The meal was served on white soap-box china on a white linen table cloth. We tidied our lips with white cloth napkins. For dessert, fried dough in various forms represented color for the evening, as it was all a shade towards ivory, but just to make sure it didn’t offend the overall scheme, it was dusted with powdered sugar.

After dinner everyone would go to Aunt Marian and Uncle Bill’s to open presents, drink wassail and egg nog, and marvel at the decorations. Except in 1953.

Now most kids have only two sets of grandparents. I was lucky. I had three. There was my widowed Grandma Zarko, my mother’s parents, Grandma and Grandpa Lopin, and Aunt Marian’s parents, Jess and Mattie Lucas, who I got to call Grandma and Grandpa, even though they were not blood relatives, and strictly speaking, not even related by marriage. But you cannot have too many grandparents, and I was a kid and couldn’t have cared less about strictly speaking.

It was decided in an adult pre-Christmas convocation, that if they were to pre-empt my asking what happens when Santa Claus dies, they had better do it when I was four. I might be too clever to sustain a belief in the Old Elf until I was six or seven. So it was that Santa Himself appeared in our living room that Christmas Eve in 1953, and in front of the whole family, not just to score a plate of cookies while everyone was asleep. Well, almost the whole family was there. Grandpa Lucas missed it completely! But I told him all about it when he got back.

One night, a year and a half later, I lay in bed wondering, and finally called to my mother to ask the burning question; what happens when Santa Claus dies? Does somebody elect a new one? Sort of like the Pope? My mother gently revealed the truth. I found it not at all calamitous. But I did have one question. If Santa Claus is made-up, who was it came to visit Christmas before last? She told me.

“Oh!” said I, “I wondered how come he was wearing a mask…”

“If you asked, I was going to say; it’s cold in the North Pole.”

“…and how come he had Grandpa Lucas’s watch on!”

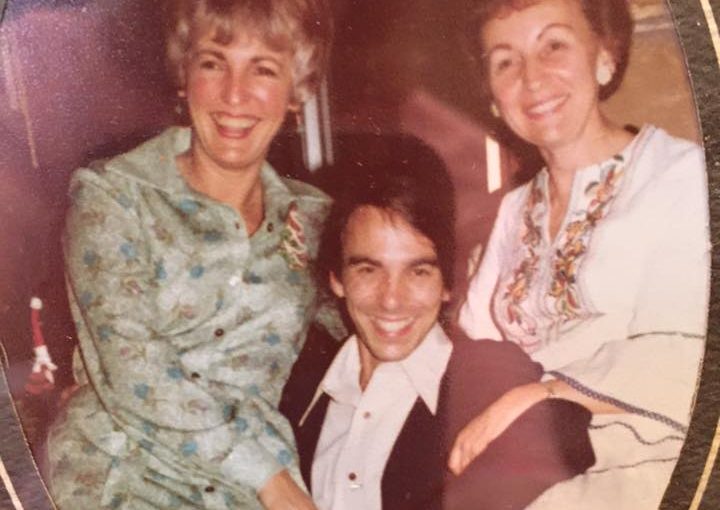

Photo: Linda, me, and Shirley — cousins.