A small ground floor room, three people, two lamps, the scent of bacon.

One of the cultural events I attended at Dubrovnik’s Libertas Festival was an evening of folkloric song and dance. One of the dances was silent. The only sounds that accompanied it was the shuffling of the dancers’ feet, an occasional finger snap, a collective sigh. The program explained that this was the dance of the refugees of war and of the Resistance, but either the description stopped there, or I stopped understanding.

During the war, the Croatian government became complicit with the Nazi occupation. A faction among the Serbs, who never got along with the Croats anyway, took that as an opportunity to cast their fellow Slavs – all of them – as the enemy. The selo of Gaic, where Petar and Stoja live, is extremely remote, and Serbian Resistance were scouring the countryside, terrorizing the inhabitants, and leaving much blood in their wake. For my cousins, staying put was not a option. So through the help of an underground refugee movement, they escaped. They didn’t know where they were going, how they were getting there, or when they would arrive. All they knew was that their lives and those of their children depended on leaving Gaic immediately.

So, Petar, Stoya, Petar’s sister-in-law, and their combined eleven children (one still a babe in arms) set off one night on a walk with little or no preparation. They walked for months. Their destination was always the next safe house (or farm, or factory, or cave) but they never knew two destinations in a row. Nor did they know when they would be able to stop walking. They only traveled by night, and carried no illumination.

There was, and perhaps still is, an ancient tradition among the southern Slavs, that when traveling by foot, if you meet other travelers you share food, drink, and dance. And when Petar and his family met other families along their route, they upheld the tradition. The food they had to offer was slight, and the dances were silent. The only music was the sound of shuffling feet, an occasional finger snap, a collective sigh.

The family crossed into Austria at an unpatrolled section of border. They were directed to a farm that had several large barns, and there they stayed for the duration of the war., working nights for their keep and staying hidden during the day.

“What happened when the war ended?” I asked, almost breathless from what I had just heard.

“We walked back. It was easier coming home. Protected zones were relatively safe, so we could travel by day most of the time. We even got rides in autos and wagons… Well, some of us did.” He translated for Stoja. She laughed and said something in Croatian. Petar translated for me.

“She says, ‘I was a good-looker in those days’, and it’s true she was. That meant we had to be extra careful. But now and then some young guys who missed their sweethearts, I guess, just wanted to be nice to a pretty girl, so she’d climb aboard with five or six of the kids, and the rest of us would have to walk double time to keep up.”

“What did you find when you arrived home?”

“Things were in sad shape, but we put them back together. Everyone in Gaic had taken a journey. Ravno was practically empty, too. But here we are,” he breathed in deeply. “Well. Tomorrow we take in the hay!”

Petar was up at dawn. He took his cow on a twenty minute trek to good pasture, every morning, while Stoja made bread and stew. He was eighty years old at the time.

“I’m slowing down. I walk (five kilometers) into Ravno and have to wait until the next day to walk back.”

When he returned from grazing the cow, the three of us sat for breakfast; a glass of plum brandy with bacon and cheese and bread, and a large pastry with the strongest Turkish coffee I had ever tasted. The brandy sent me for a loop, the coffee wired me. I didn’t know whether to scream or fall asleep. (They did this again at “tea time”, mid-afternoon.) Then they left for the hay field. I followed best I could.

The hay field was a plot of land that measured maybe a quarter of an acre, that they had planted in alfalfa. Once I had caught my breath, Petar explained that rain was expected the day after tomorrow, and that rain would spoil the hay.

“So, we do this right now.”

“Great! What can I do to help?”

“Sit right here on this rock.”

“Okay.”

“Watch. Tell your father and uncle what you see.”

“I’d love to work if you show me what to do.”

“Sit. Watch.”

So, I sat and I watched, feeling useless and guilty as hell.

Petar had sharpened his scythe the previous evening, and now displayed an almost balletic mastery of the tool. The grass fell into neat rows, Stoja raked it into piles with all stems lined up, and onto a large cloth that had a loop at one end, and ties on both. Together, she and Petar rolled the fabric into a kind of burrito stuffed with hay, and tied it off. Then Stoja put the padded loop onto her forehead, and carried the roll on her back to the hay barns. They were not far away, the barns, but this was clearly the most efficient way of filling them.

While I sat and watched my cousins work, five men on horseback rode past. They were dressed like the dancers in the folkloric festival I’d seen, only they looked, and were, real. Petar and Stoja waved, the men waved back, a few words were exchanged and the group moved on.

“They’re from (the forgotten name of a nearby village). Muslims. Good, honest people, excellent neighbors. They’re hunting today, small game. They raise sheep, actually a kind of goat suited to this terrain, but they look like sheep. The best cheese!”

After another hour or two, Petar sniffed the air and announced that the rain had changed its mind and would come a day later.

“No need to hurry, now. Time for lunch.” The scythe and rake were leaned against a barn, and we strolled back to their house.

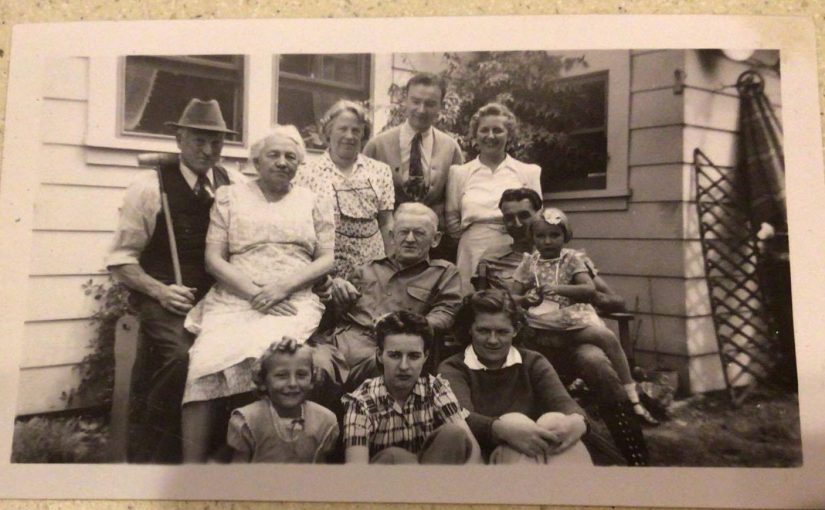

Photo: a modern, town version of the silent dance.