I looked at the weather for the next few days, and it is gorgeous for the weekend, then on Monday and Tuesday it dips to highs of +7C (about 45F). That’s not really cold, but neither is it gardening weather. Not for me, anyway. So I decided to forestall preparing the zucchini soup until Monday so I could enjoy the milder temperatures while they lasted. I had visions of repairing the corners of the umbrella and letting it spread magnificently across my little courtyard, then of lounging under it like a Roman emperor at his villa in Capri.

Didn’t happen. I hadn’t accounted for a chill wind and once I noticed, didn’t feel like sitting in it. One may not actually contract viruses from the cold, but why test the theory now? I managed to do a few simple tasks outside, but mostly I spent my day indoors.

I did make it to Metà at 15:30, the quiet time, and sure enough, there was no one in line and only me and two others in the store. Gabriele was on the phone as I walked in. I didn’t catch any of the conversation, but he was earnestly engaged. I went about collecting ingredients for the soup, and other basics, and returned front to an empty line.

My friend Anna came in. We did air-kisses, she smiled broadly and said, “Just like normal!” I was glad to see the smile and welcomed her good humor; last I saw her she seemed to be having a hard time adjusting.

Gabriele was still on the phone as I checked out. I couldn’t tell if it was the same or a subsequent call, but he was saying, in a most cordial manner, “…at Liceo Artistico (The Arts High School).” (pause) “Right at the bottom of Via Roma. Yes, just off Piazza Cahen. I have a green Ape (a kind of tiny three-wheeled pickup) will that be enough?” Then I became absorbed in the logistics of bagging – as Gabriele was otherwise occupied – and missed how the conversation progressed.

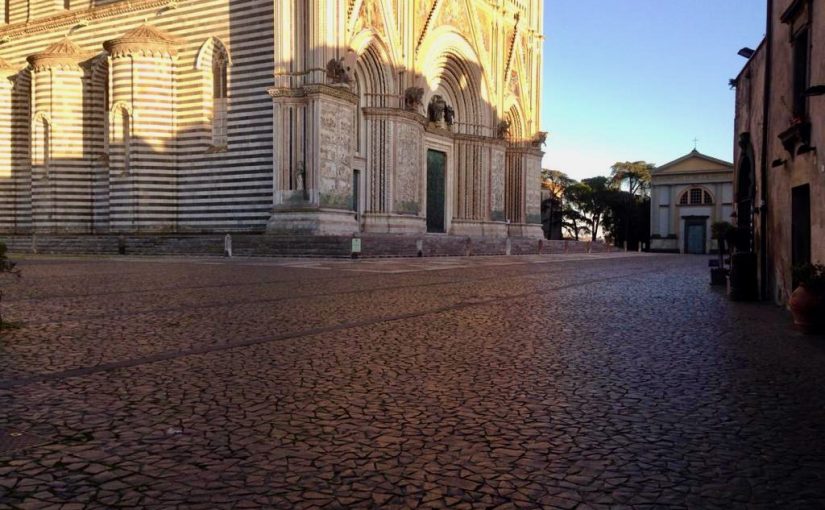

It sounded like he was arranging for a delivery to a plague town (though Orvieto has not been severely hit) – “Leave the merchandize at the gate with your bill, we’ll arrange for payment via our agents in Padua.” I flashed on his comment of a few days ago that everything took three times the effort of a week before, and as I reflected on shelves that showed a bit more paint than they did even on Tuesday, I wondered if that ratio were now up to nine times the effort.

As I rounded the corner to home, one of my neighbors was standing at the front door to his building enjoying a smoke. I think he just moved in a few months ago – at any rate, we only began exchanging greetings a few months ago.

“Salve,” he nodded (sort of like, “howdy”, only more Roman).

“Salve. How’re you doing these days?”

“We’re well. We have to do this, don’t we? So we do it. All we need is a little patience.”

“A little? A lot of patience.” I responded in my loud American voice.

He looked puzzled.

“Sorry. A little. It’s not really so bad.” Or at least that’s what I wish I’d said. Instead I bade him a nice evening and rushed through my gate.

Part of that sudden escape was simply because my Italian-readiness in speech has degraded during these last few days of isolation, and I didn’t trust myself to correct my over-reaction in a way that would make sense. A larger part of it was that I had shocked myself with the exaggeration, however mild, that had taken over my personality. I had vividly experienced a cultural divide concisely expressed in an exchange of a dozen or so words. Perhaps my young neighbor had not experienced those events that required more than a little patience, personally, but the knowledge of them has been passed down in the communal genetic code. As rigorous as the quarantine is, it pales in its demands on the community compared to – well, pick a decade. There are heroes aplenty in the health system, the government, the police, even in the Gabrile’s and delivery folk of the nation, but all most of us have to do so far is to stay at home.

“All we need is a little patience.”

I went out again immediately, before I lost impetus, to the fruttavendolo (produce shop) for zucchini and shallots. The shop is owned by a high-energy, bright-eyed young Orvietana who, after at least two years of regular conversation over purchases, I am finally beginning to understand – a word here and there. I usually am able to respond comprehensibly if not always appropriately, but today I could tell from her expression that it was too much trouble to figure out what I had meant by what I had just said. I dropped stuff, fumbled the change, and stammered my goodbyes.

I have to start with the online lessons again, because the slide is not going to reverse itself. Sometimes it’s a blessing to be told to stay at home.

The photo of Metà is from before it was renamed “Pam”. As a sophomore in high school I developed a crush on a girl named Pam, and, rationally or not, I don’t want my supermarket to share the name. She moved to Alaska, by the way.