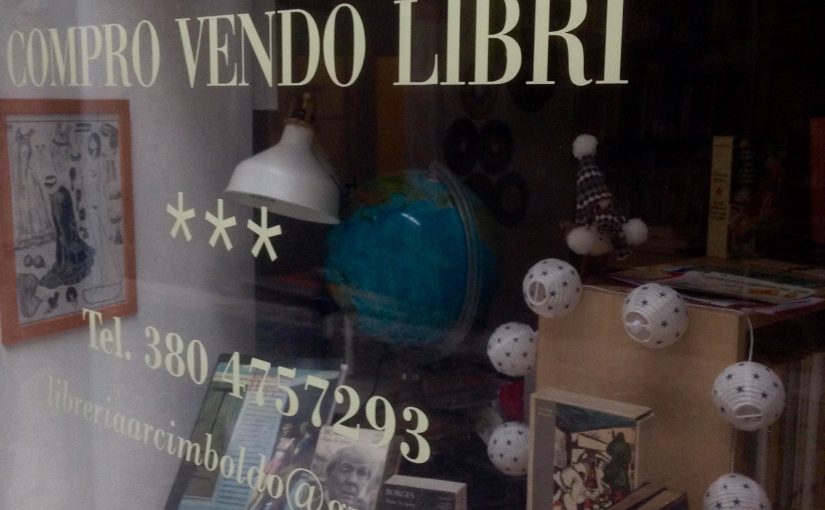

There is a young fellow here called Gianluca who owns a used-book store on Via Filippeschi. I pass his shop often. When he has no clients, he’s behind his computer diligently pursuing his livelihood. I have no idea what specifically he does there at his desk, but I admire him, his persistence, and his young man’s commitment to books in this age of digital texts. Sometimes I feel personally responsible for his store’s continued viability, that I need to buy books from him I’m not able to read just to help keep his shop open. (I’m finding out that I’m not the only one to feel that way.) Today as I passed his store – closed for riposa, the window gates open and a string of LED’s decorating his display of old books with dancing titles – it suddenly hit me what his position at the desk reminds me of.

I was playing with my friend Jimmy Galindo in his driveway when we found them. Boxes and boxes of paperback books that a neighbor was apparently throwing away. They were mostly classics from a high school reading list, books that the owner seemed not to have any interest in re-reading. “We could start a library,” Jimmy enthused. As a new state-of-the-art library had just opened halfway between our houses and no more than a block from either, the idea struck me as ludicrous. At first. But as we talked, together we glorified the notion, and a few minutes later I was totally jazzed.

Over the following weekend, I could think of nothing else. Even my ten-year-old personality derived great joy from cataloging and organizing, and that there was a generous supply of books upon which to base the project, a library – grass-roots, home-based, a neighborhood library for kids, not a branch of the county’s vast system – seemed a brilliant idea. As I mulled it, I concluded that my impressive collection of Disney comics would be an apt compliment to Wuthering Heights and Pride and Prejudice, neither of which I had heard of previously. My excitement carried me back to Jimmy’s to make sure the books had not been carried off. They were still there! Some had been rained on, but were salvageable. I carried them home, a shopping bag at a time, over a long day of walking. Jimmy voiced enthusiasm, but I could tell his interest stopped short of cartage and actual physical organization. That’s okay, it would return in full flower when he saw the idea realized. I dreamt of greatness.

My mother had long since come to understand that when I had a project in mind, the path of least resistance was to make sure I did no damage to the furniture and let it play through. So, as the bags of books appeared along with the explanation for their arrival, she shrugged and smiled and said, rather wanly, that it might be a good idea, except who would be the clientele. I angrily dismissed her unimaginative and pessimistic commentary, and forged on.

In a week’s time I had stripped my room of personal décor so it would have the proper institutional ambiance, sorted and shelved all my literary treasures by title, author, and date, and typed up a list that would have to do until I had the money and time for a proper card catalog. I designed a sign, found some old railroad board, loaded up my FloMaster refillable felt tip pen (a prized possession), and went to bed that Friday night knowing I was ready for business come morning.

The sign was created and hung on my bedroom door first thing. After all, the fliers I had distributed to my classmates listed hours of operation, and the first rule of public service is consistency. So at 8:30, the announced hour of opening, I was at my desk behind an ancient Remington typewriter, the kind that proudly displayed its working parts, ready for an influx of eager young readers.

At ten, I had a sinking sensation that perhaps I had neglected something we would now call market research. At about eleven, my mother, probably steeling herself against what she accurately imagined would be my annoyed response, endeavored to be my first customer. I played along, knowing it would amuse her, but was privately perturbed. She checked a few things out that I was fairly confident she would never read, but I was pleased that my system of date stamps and cards (which I felt improved on the county’s model) worked so cunningly well.

At some point my mom called Jimmy’s mom, or at least I suspect that’s what happened, and the afternoon was a rush of eager literati. This continued for a couple of hours. We talked comics. It was fun. But Sunday was a dud; I figured because people had other stuff to do. So, despite my late opening time (in deference to churchgoers) I closed early at two. The next weekend, was slower, and my hours grew shorter. I had distributed another round of fliers to classmates during the week, and many had vowed they would visit, but I imagined there were family outings, maybe homework that had been put off, so I endeavored to read a classic from the library’s significant collection – before its time in my literary development – at which I failed. The third weekend someone asked me over to play, so Saturday hours were very short, and on Sunday the library didn’t open at all.

I don’t recall the actual demise and disassembling of the Neighborhood Library for Youth, it probably happened gradually. But that moment on the first morning when the penny dropped – that my dream of service was perhaps not shared by anyone else, not even my own mother – has lived with me through innumerable, and what have often seemed to be hauntingly similar, projects of arguable viability. The memory has corroded numerous attempts at my establishing a useful place in the world: the theatres, the cafe, the writing. “It might be a good idea, but who’s the audience?” I’ve been fleeing from that spot behind the ancient Remington typewriter all of my adult life.

So, upon passing Gianluca’s store today I suddenly wanted to write what would mostly be about a failed fifth-grade, and totally daft, library project. But it would also be about what strong patterns can radiate from a single moment at the age of ten and the significance they may have to later life. Metaphorically speaking, the moment is when you notice that the arch you just labored so hard to erect has no keystone.

Installed behind his modern-day Remington, Gianluca shows genuine courage in his dedication to what may appear to be a Quixotic waste of energy to the casual passerby. But you know what? So did I seize courage with my childhood library, even frozen as my omission dawned behind the skeletonized typewriter – and later, behind the electric one on which I typed notes and press releases for the theatre I started in San Francisco and the caffe in Santa Cruz, and even later, behind my own computers that I pecked away on during my stints as theatre administrator in New York and Scranton. And maybe even this blog, highly redundant as it is in the grander scheme of things, requires courage – “Who’s the audience?” – as do all blogs uploaded with good and generous intension. And as do all young persons laboring at their dreams.

Donald Duck is always throwing himself into far-fetched but alluring schemes that lead to grave consequences he never learns anything from. Rage and frustration shadow him everywhere. And it makes us laugh; because we recognize his dilemma, of course, but also I think because we aspire to be otherwise. He’s just a duck. We hope, at least, to behave as something more evolved than that.

I’m living in Italy now. It’s taken me, at a minimum, two years to maneuver myself into this reality, an urge and a dream I’ve had since I was charmed by my Italian neighbor’s seventieth birthday party when I was fifteen. Rage and frustration shadowed my many attempts at convincing myself that I could never find a way to live here. And, lo, I am here and nothing in my circumstances these days seems to depend on my having an audience! If that’s true, I’d like to think it the gratefully accepted wages from a life of Quixotic courage.

I live here because life is love, love is all, and I do not miss the inner Donald (Duck.) And because this hard-working city clings to a communal dream that I find glorious and worthy of my unembarrassed support.

Quack? No. “Salve, Gianluca! Cerco un libro. Può aiutarmi?”

Oh, my goodness. Well over half the opportunities I look at read more or less like this:

Oh, my goodness. Well over half the opportunities I look at read more or less like this: