How long before we become restless and want to sit down to a really good, wood-oven pizza? Compliments to the pizzaiola! Let’s have a dolce! Not long. I’m already there.

People have compared the lockdown to wartime. I’m not old enough to remember the second world war, only that it was frequently referred to when I was a child, and simply as “The War”. But I know people here who have real memories of Orvieto during the German occupation and Allied bombing raids, and I have a feeling the comparison, if made at all, strikes them as highly superficial. It’s quiet, there is a threat lurking somewhere that has caused it to be quiet, but no fire falling from the sky, no death in the streets, no fearsome soldiers marching in tight formation through piazzas.

It’s just profoundly quiet.

I walked today, as ever. Around the house I feel that I move like a man of 180 whose health is not particularly sound. Five minutes on the street, I’m a fit forty-five. So, of course I walk. And if the town was empty on a weekday, it is even more empty on a Sunday afternoon. But how can that be? There was nothing left to cancel, no shops or restaurants left to close. Maybe the repeated experience of emptiness drives the emptiness into one’s organs, makes it hyper real.

I took a long time to get going this morning. Having no one to see, nowhere to go, and a Sunday, robbed me of motivation even to dress. Around noon, my friend Ida called.

“Are you up?”

“I am up.”

“I’m about to walk with Amber (her Jack Russell terrier) and wonder if it would be okay if I dropped by. Just to see a friendly face!”

“That would depend on how soon you’ll be here.”

“Fifteen?”

“I’m up but not ready.”

“Oh, then, that’s okay.”

“But raincheck. I’d love to see you.”

“I’m thinking of renting Amber out to people who need an excuse to walk.”

“I’ve been thinking of offering to rent her.”

We concluded and hung up. Ida has a charming, funny, and intelligent husband, but I reckon we are all of us getting a little tired of the sameness of the days. The food. The routine. The company.

When I finally got out, I passed Igor on the section of the Anello near Porta Maggiore. Igor is a brilliant presence in town – kind, friendly, energetic, and with a superb aesthetic. We exchanged the usual greetings, two meters apart.

“Are we criminals for being out like this?” I asked, only half joking.

“We are allowed to walk, even without the dog.”

“Good! Because I’ll go mad if we’re not.” And we both hurried on.

But that does reflect a change. As the novelty of a town utterly transformed wears thin, many of the people I pass seem wary, sad, unsure if they should smile or say hello. Not everyone, to be sure, but many more than four or five days ago. It’s almost like being out is in itself wrong, even if there is plenty of distancing and no contact. We avoid each other, guiltily.

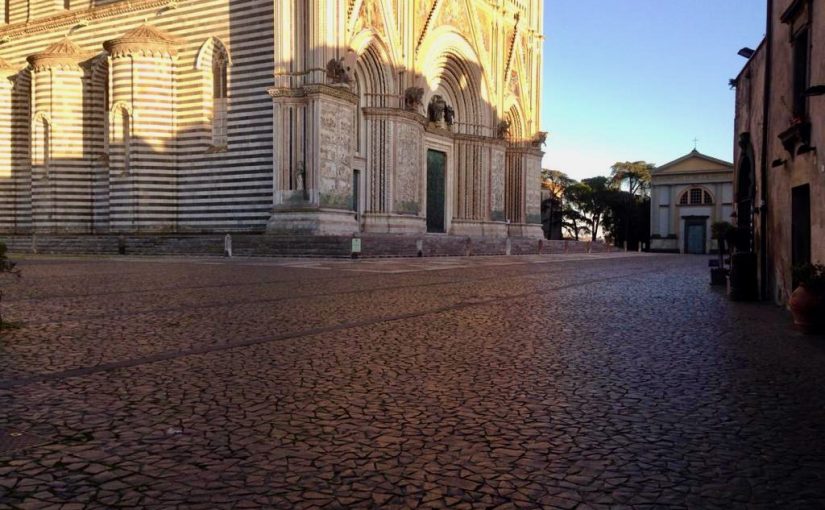

I stopped to take a photo of Piazza del Duomo close to sunset, deserted, a vast expanse of untrod pavement. The local police cruised by. I quickly turned towards the stairs, and moved with great purpose. They were not at all interested in me, but the occupied city parallel must strike a chord beyond what I regard as rational.

On the other hand, children who are at home instead of school, instead of playing or wandering, instead of being royally escorted in their prams well past there being a need, at home instead of learning the vital skills of social interaction, these housebound kids are making signs. Most include a rainbow, some have handprints, self-portraits and representations of relatives – and the words Andrà tutto bene, Everything will be fine. Their art is being hung from windows and on doors, little by little, all over town. Apparently, children are not as vulnerable to the virus, and in that possibility may rest the key to effective treatment and cure. It is fitting that it is children who are crafting the town’s messages of hope.

Tonight at nine we turn off the lights for one minute, and illuminate our houses with flashlights and phones. Because we can. It may not be pizza, but it is an expression of community, and community is what we really miss.