I got weepy today. The causes were various. Sometimes, I found myself sobbing at a story (heard on a podcast) of remarkable courage. Other times, I sobbed from the sheer magnitude of sadness we are experiencing as a species. There was more weeping in response to joy or inspiration than to gloom, so that it wouldn’t stop all morning was not intolerable, but so many things set me off that it must somehow be connected with grief. We’ve lost so much in these past two months, not the least of which is our ability to pretend that “we can go on as we have done, just let us get past a certain marker,” with anything.

Every now and then my mother would suddenly say, “Why do things have to change? Why can’t everything just stay the same?” I preferred to accept the absurdity of the wish to letting it disturb me. Nothing exists apart from time, and human time is measured by change. But lately, I have come to recognize where that complaint came from. It’s a deeply human place, no matter that it lacks logic. Change may be the most pervasive aspect of living, but when there is too much, it’s natural to feel around for the brakes – even when we know there are none.

I, on the other hand, am wired to seek change, to like it. That’s one reason I was so drawn to theatre, where everything is in a constant state of fascinating flux. Rehearsals are a process that the artist may, at best, be able to guide, but the end result is always a surprise to me, even when I pretend it’s exactly what I was aiming for. I remember in my twenties hearing another young director complain rather cynically that if you achieved ten percent of your vision for a play, you were lucky. My reaction – and I don’t recall if it was ever expressed – was “Ten percent would be awesome! I never see anything turn out the way I expect. And that’s why I do this!”

The challenge I have always faced is how to take that same creative freedom and apply it to other aspects of life.

If you’re expecting me to answer that, you have a long wait ahead of you.

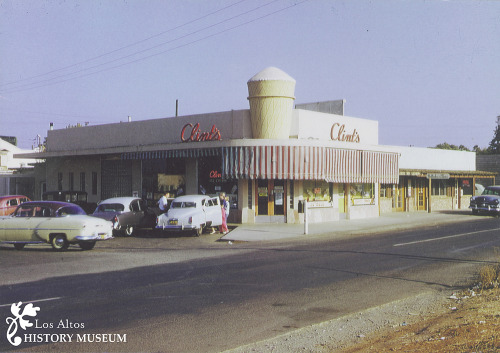

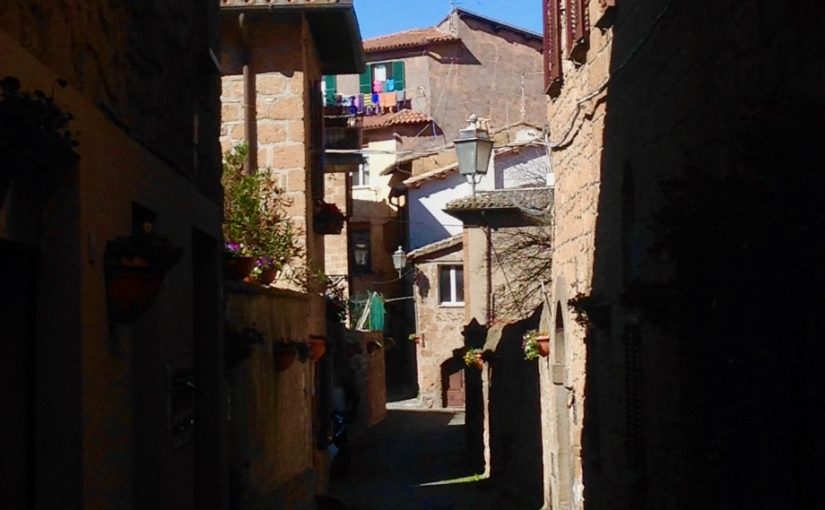

The first year or two that I lived in Orvieto, personal change was exhilarating. There was the language, the culture, there was not getting lost. And there was plenty to brag about to folks back home. No snow to speak of, a walking city that is also affordable, a vivid cultural life. And while all of that is still true, the suspension we now find it in is strikingly similar in feel to the week during rehearsal when the staging has been worked out, interpretation is beginning to reveal itself, and now it’s time for the actors to go off book – that is, to begin to work with lines memorized. Those four or five rehearsals are full of surprises, too, but most of them are terrifying.

I wish I could draw a more exact parallel between being in lockdown and those getting off book rehearsals, but there probably isn’t one. However, because I’m a director, I will try, anyway.

Both are about striving for what, at the time, seems an unknowable outcome.

Up to the point of the actor’s leaving the script in a backpack and going onstage without the happy crutch of the written word, marvelous work has been done. There are moments of transcendence, perfection, and astonishing emotional courage. There are seeds of camaraderie and ensemble effort that send the spine into flourishes of ecstasy and melt the heart. There is great promise and hope. Then for the next twenty or so rehearsal hours, almost all of that disappears while everyone tries to be patient with an unpleasant mechanical process.

Until recently, I thought that with prudence, we would slowly make life safer during the lockdown until a tipping point is reached when all the pieces begin to find their places, and we rapidly move towards a new equilibrium. Right now, today, I’m not so sure. It seems impossible that this experiment we are a part of will ever resolve at all, let alone favorably.

And that is when my theatrical experience proves useful, because that’s exactly the way I usually feel after a first run-thru off book; hopeless, while still trying my best to put on a favorable face for my dear actors, for without hope they will never get through technical rehearsals when once again everything will fall apart – only more severely than before.

But in the end, live theatre has the best on-time record of any human effort. Come what may (and with notable exceptions) the show always opens as announced. Of course, it is wrong to suggest that a pandemic can be explained away by a metaphor, especially a theatrical one, and all successful openings are backed up by months of careful planning, wise casting, solid staffing, deep analysis, and selfless teamwork. (Creative freedom is wonderful, but it doesn’t come cheap.) But if we relinquish the notion of a logical march towards a foreseeable resolution, what happens might just be, as so many plays end up being, far better than anything we anticipated.