A balloon, a piano, a grandfather clock, and a blonde.

One of my dad’s regular customers was a gentleman confusingly named Gain John. He and his family lived in the neighboring city of Palo Alto. Every now and then the Johns would invite us to dinner. Theirs was a large kitchen so we supped informally. I don’t recall if they had a dining room, or if we were in the kitchen by virtue of a perceived level of comfort with each other’s company. Mrs. John, whose first name I forget, had a nice collection of Revere Ware pans hanging on the wall, all their copper bottoms gleaming without stain or spot. My mother never failed to mention them on the way home; to her they represented an impossible dream.

At that point the Johns had only one child, a girl of maybe four or five, blond and sweet. I was a wisened ten years by then, and being an only child, took to her as I would a little sister. One I adored and wanted to nourish.

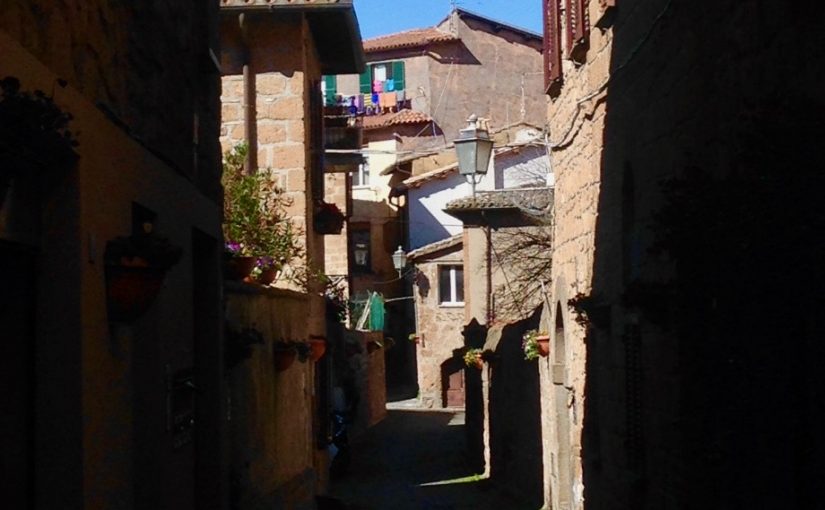

The street they lived on was narrow and woodsy, there was a grey picket fence, a long winding walk through a tree-filled garden to a kind of external hall that led into an irregularly shaped office to the right, and to an impressively Julia Morganesque front door. The living room was large. To the left was a sunroom packed with plants. Straight ahead, a baby grand piano. Next to the fireplace to the right, an elaborate grandfather clock with what seemed like a dozen dials that colorfully measured various astronomical events. The floor was covered with a thick Persian rug. Their home was as unlike anything in our family as I could imagine.

So, into the aftermath of one of those kitchen dinners appeared a balloon. And before long, four adults and two children were standing on that beautiful carpet and batting the balloon in a circle. I made a special effort to send it at little girl height so she would be a part of our sport. The adults did the same for me. It was like a dream. When we played games in our family, there were rules, or horseshoes, or fake roulette wheels, and there was lots of vocalizing; shouts of surprise, victory cheering, bad luck groaning. That night at the Johns’ there was the pong of a passed balloon and an occasional murmur. And we were all one society, ages four, ten, forty-something, and fifty-something. I held onto that memory like a precious gemstone.

One evening in 2005 while I was on loan from Scranton, my mother and I, bored with what broadcast media had to offer, began to randomly reminisce. The Night of the Bouncing Balloon came up. Well, to be sure, she had no recollection of it at all, but she remembered Gain John, and how she was always reversing his name in my father’s ledger book when she recorded bills and payments. I described their house. She remembered that, too, though not quite as vividly as I did. She also remembered the Revere Ware, but denied any emotional crisis around its immaculate display.

“Where was that house, exactly?” I asked.

“I have the address somewhere,” as she pushed herself out of her rocker and shuffled to the breakfast room-made office. In a deep drawer she had every address book she’d kept for sixty years.

“That would have been 1960?”

And so it was found.

“Let’s go look them up,” my mother enthused.

“Well, we could drive past, see if the house is still there.”

“And if it is, we’ll stop in and say hello.”

“What if they sold the place? They probably have. I doubt anyone we know is still living there. And what if they don’t remember us? And why should they.”

“We’ll go tomorrow morning.”

And so we did. I drove her Toyota to the discovered address. The house was on a corner, as I remembered it, and obscured by trees, but it lay only a dozen feet off the widened highway, and there was a semi-circular driveway that went from side street to main road.

“Turn here.”

“Why?”

“So we can see it better.”

I did.

“Now go into the driveway.”

“I can’t do that!”

“Why not? We’ve come this far, we can’t just drive past.”

“We’ll drive in and look.”

We did.

“That’s the place alright. I remember that little hall that led to the front door. And inside was a sunroom, and a piano, and a grandfather clock. Well, we’ve had our look, better get out before they call the cops.”

I started to pull slowly away, and Mom had her door open and was ready at 94 to leap out of a moving vehicle rather than to have her curiosity curtailed.

“Okay, we’ll go in…” but my suggestion came late as she was already halfway to the front door.

I sprinted ahead, knocked, and grimaced.

A woman, blond, about six years younger than I, opened the door.

“We were just driving by and thought it would be nice to say hello. I’m Ann Zarko, and this is my son David.”

I stammered apologetically and waved.

“Oh, yes,” said the woman, “Mr. Zarko was Dad’s mechanic.”

We were invited in. The sunroom was there, but no plants. The piano was there, too, and in about the same position. The grandfather clock had been moved, and the Persian replaced with something from the 1970’s.

“Are you here for the memorial?”

We responded blankly.

“Oh, today was Dad’s memorial. He died three weeks ago. We’re just back from a celebration of his life. It was lovely.”

“We just showed up,” and I told her why and how. We stayed an hour.

Photo: This may actually be the house, which would be a hugely lucky search.