In my late twenties and early thirties, I lived for two-plus years in San Francisco. A small Equity Waiver house was bequeathed to me by its creator, who said she chose me to pass it on to because I was a man of the theatre. I was thoroughly smitten by that characterization, and by the city’s theatre community, and stunned by what seemed at the time to be extraordinary luck. I was also, as has often been the case with my leaps into the unknown, thoroughly clueless. But I understood the basic laws of improvisation, and I can say with some assurance that the group I formed had a good time laboring under my ramshackle leadership.

Our little company became friends with the theatre folk at the Women’s Center, and I became friends with a grounded, talented, and very interesting playwright who worked there. When she found out that my father had recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, she gave me tickets to a play she had written about her mother’s encounter with the same. The script echoed future experiences of mine, was solidly written, and lovingly performed. After a dozen scenes of courage in the face of a slow fading away, the last scene featured her mother, completely restored, saying, “the Parkinson’s is gone”. I was swept up in hope.

“Your mother recovered!” I enthused after the performance.

“Only in my dreams, and in the dream end to my play. Do you think it’s a good ending or is it confusing?”

“It’s the perfect ending. It’s why we make plays. Maybe someday medical reality will catch up to the theatrical.”

I felt foolish for having fallen for it, but I also devoutly believed that the disease could be beat, or at least trained to behave. Such was not the end of my father’s story, however. His last year and a half were a misery.

Last Thursday my excellent physiotherapist, Katrin, took me to a neurologist. The months of inactivity that followed an injury to my Achilli’s tendon really exacted a price regards my Parkinsonian symptoms. I was slower, more hunched, hoarse, and shuffling to an extent I had never been. He gave me a crash course in synthetic dopamine replacement that would, as he said, leave me symptom free in two weeks. I don’t say no to such promises, so I began that evening. Since then I have been hollow and shaky, have had tighter-than-usual muscles, and I’ve slept no more than four or five hours a night. Presumably the road to mitigated symptoms crawls through a dark forest teeming with ugly spirits. I will persist, however, for hope, once granted, is not a thing to be carelessly wasted.

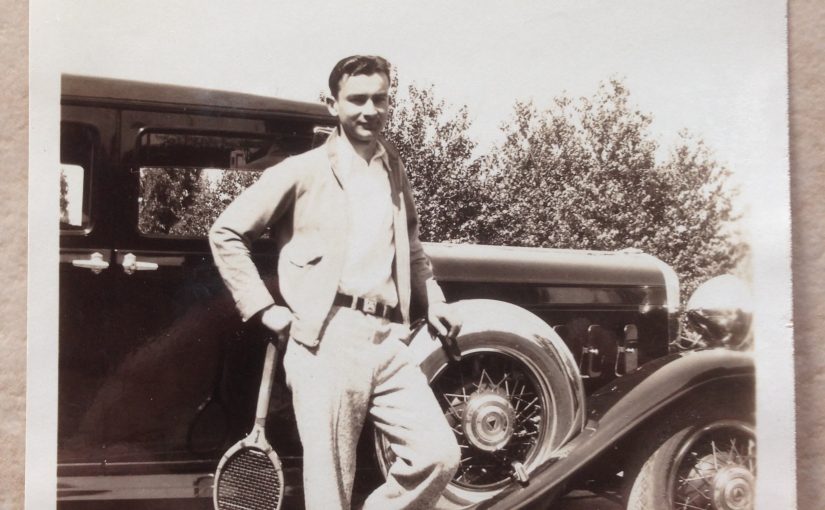

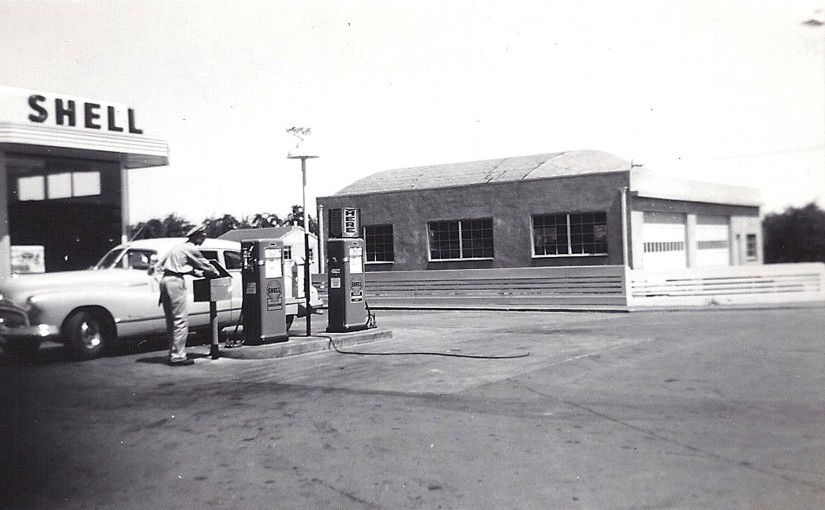

My father’s life-long hobby was the restoration of antique (pre 1925) automobiles. From the time I was four to a year or so before he died, he worked on a 1912 REO Runabout that was set up on blocks in our basement. He and his brother had discovered the machine under a collapsed roof of a lumberyard in San Mateo. What wasn’t metal had rotted away to faded scraps, but he was determined to salvage a functioning automobile from the pile. He had seven other cars in much better shape he would also work on, but the poor REO had captured his heart.

One visit years after he was diagnosed, he greeted me excitedly at the side door to our house.

“I want to show you something,” he said, leading me to the basement. He plugged in the overhead tube lights, and stood back. “I finished yesterday.” He had restored and installed the rear axel, chain driven, a mechanically significant event. “Took me all week.”

I congratulated him, then struggled with the realization that the gear box that housed the chain was on the wrong side.

“Maybe I don’t understand how it works, but…”

He saw it as I did. Truth through the eyes of the son.

“But I’m here for two weeks, we can redo it together. It’ll be fun! You can teach me things.”

He turned, unplugged the lights, and went upstairs without me.

The rear axel to the REO was his “the Parkinson’s is gone” moment. It was his theatrical statement of altered reality. After that, he gave up. His best friend Les finished the REO after Dad died, lifting it from its basement hideaway into the air and light of the six car garage Dad had built after he retired. I helped in my limited fashion. Then when it was finished, my mother sold the car to a fellow who adored it, improved it, and (by now) probably passed it on.

I will give the drugs the two weeks the doctor quoted me, then if I can find a neurologist versed in the use of Mucuna Pruriens – levodopa in its natural and possibly more effective form – I will ask questions. And all along the way I will imagine what a total healing would be like, see if I can coax an unexpected resolution (aka a surprise ending) into being.

I am, after all, now and always, a man of the theatre. One is not meant to deny one’s nature.