The first foreign language I tried to learn was Russian. I studied four years in high school and became good at reading and writing, and in certain controlled academic settings, I could speak fairly well, too. Friends of the family were born in Russia, and one evening at supper we gave conversation a try. The effort was brief as they didn’t want to embarrass me – which to a 16 year-old was highly embarrassing. I never tried again.

Five years after high school, I visited our family’s ancestral villages in Croatia. Croatian is a Slavic language and shares some grammar and like-sounding words with Russian, but it is heavily influenced by its historic (and many) occupiers, so is also laced with Latin grammar on top of the already complex Slav, and carries a huge vocabulary of object names derived from Italian, German, and Turkish. In short, my Russian almost made trying to learn Croatian more difficult. My oh-so-patient cousins struggled with me through tortured sentences frequently interrupted by my pulling a dictionary out of my back pocket. After a couple of weeks, we breathed a collective sigh, and I returned to California.

Three years later I stayed in Firenze for a few winter and spring months, and made a feeble effort to learn the language. I was generously accommodated by an American friend, who, when we were together (which was almost daily), used his fluent Italian while I pretended to understand what was going on. In an effort to catch up, I read comic books. I must have learned something because I vividly recall giving a young Italian couple directions to Palazzo Pitti (a triumph!), and I was able to order coffee and buy groceries, but I had not a clue as to grammar or structure.

At the end of that trip, I revisited Croatia. On the train from Trieste to Dubrovnik, I shared a compartment with a scholar. She spoke literary Croatian, but used a less-educated form so I could understand her, and somehow I did, and somehow we managed a simple conversation.

In Dubrovnik, I was met by a cousin who drove me directly to Zuljana where most of my mother’s family lives. We arrived at Veronika and Marko’s house quite late. Fifteen cousins were waiting in the kitchen. Everyone had questions. I was too excited and too tired to be intimidated, so I answered them. This went on for some time when someone finally said, “You must have been studying these three years! You speak so much better.” I’d not uttered a word since my previous trip. The difference was that at that moment I had simply stepped out of my own way and allowed myself to function at whatever level I could. That sudden facility for Croatian waxed and waned during my three weeks there, but the good days were always better than the last good day.

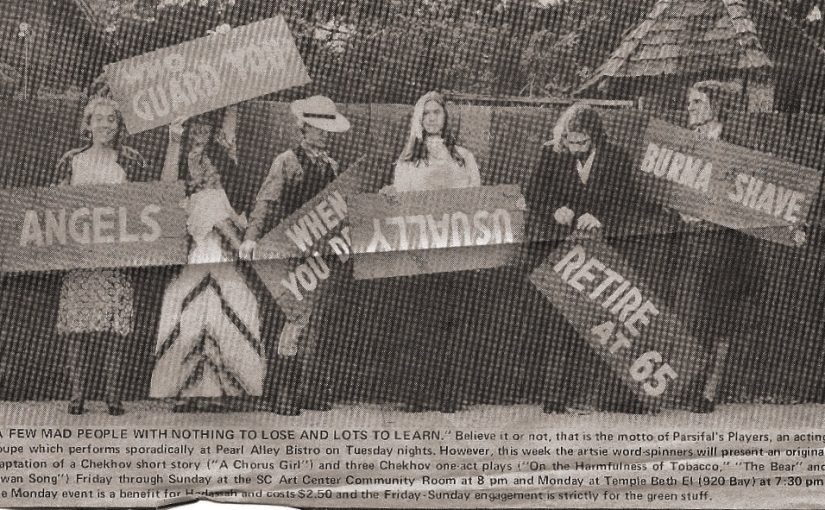

A year or so later, that same friend from Firenze and I wrote and produced a play in Santa Cruz, California. It was a large-cast affair, and I asked everyone I knew who could walk and talk at the same time to audition. One workmate at Caffe Pergolesi was perfect for the male ingenue, but when I offered him the role, he declined. Then stuff happened, and for reasons later forgotten he did the show anyway.

Last March, the male ingenue – a bit older now – and his wife decided to spend a couple of weeks in Orvieto. In preparing for the trip, he mentioned something about my basically having saved his life all those years ago in Santa Cruz. When he arrived in April, I asked him about that remark; I had no recollection whatsoever of being in any way heroic, then or ever. He explained that he had been depressed. He had turned down the role I offered because he felt that before he could bring anything of value to the community, he had to clean his own psychic house. I apparently read him a riot act, told him that the only way he was going to spruce up his emotional life was in the midst of contributing – he just had to jump in and do it. So he did. We ended up creating a theatre workshop together that lasted three years.

I have a small community of people from various backgrounds, skills, and associations assisting me with my recent journey through the hills and valleys of physical health. I have a larger community of loving friends and familiar strangers greeting me daily with smiles and unspoken encouragement. I have a world-wide community of friends and family who have been present, in one form or the other, throughout these trials and confusions – you, dear reader, are notably among them.

A few weeks ago, one of my far-away friends wrote in response to my recent blog that I seemed “obsessed”. The word played through my mind. Suddenly, today his comment made sense, and all the elements listed above snapped together. I had fallen into the trap I most wanted to avoid from the beginning; I had, on some level, accepted the role of a PD victim. The oft repeated monologue goes, “Oh dear, I must be so careful, the situation is so delicate, what if I’m doing too much or too little, or what if..?”

In the past few days my Italian has gained in fluidity, if not fluency, to a surprising degree (depending somewhat mysteriously on who I am talking to). This happens periodically, and is always connected to my giving up exaggerated notions of having to speak correctly – to my not getting in my own way.

With the health adventure, it’s past time to relax and let the body play through both its problems and triumphs, and most particularly, through its responses to the treatments I’ve been given, however twisty and unpredictable that path might be. As in learning a language, there needs to be space granted, notions dropped – not every grunt, nor every hour, nor every rebound must be perfect or lasting. Every good day tends to be better than the last good day, and so long as that is the case, it will sustain me. This is not unknown territory.

Because I stepped out of my own way, the day was wonderful. Whether I feel better and therefore stronger, or I feel better because I am acting stronger, is a question for the ages. Or perhaps there is no question at all, and it is as the old Shaker song says, “By turning, turning we come ’round right.”