I woke early. And – a minor miracle – I got up, got dressed, and was on a morning walk by 07:30! That has been a goal of mine for an embarrassingly long time, and somehow this morning – and I don’t know why – it happened almost on its own. After traveling in circles for fifteen or twenty minutes, I began to notice others bustling about, carrying shopping bags and dragging carrelli (carts). When one of the others was someone I knew, I inquired.

“Natasha, is there a market today?”

“Yes! Last week it started again on Thursday.”

“Like we can buy stuff and walk around?”

She laughed, “Exactly. Much smaller than normal, but we can buy stuff and walk around.”

I turned towards home, fetched my bag, and joined the flow towards Piazza del Popolo and Piazza Vivaria.

A friend had sent me a photo of what resembled a mini version of market towards the end of last week, with the caption, “it looks as if they’re experimenting with an open market.” It’s not that I disbelieved her, it’s that I checked on Saturday (the second market day), the squares were empty, and I put it out of mind as too much to wish for.

This morning, everyone moving in the direction of market behaved a little like they were going to check out an alien landing – all we needed was a score from a Spielberg film to back us up. And upon arrival, it was indeed a bit like that. There were maybe a third of the usual vendors. Barricades with signs were everywhere, and they were garlanded with police tape. Shoppers stood at three or four times the required distances. Pairs of police representing every level of law enforcement dotted the square. And of course, none of the vendors were in their usual spots.

My main interest in market is dried fruit and nuts, and my preferred frutte secche man is Fabrizio. So, I set off in a round to see if he was there. I found him rather easily, tucked into a corner of Piazza Vivaria near the pass-through beneath the stairs at Palazzo del Popolo.

“Fabrizio! Come va?”

“Ola! Davide! Va bene, tu?”

Fabrizio is always friendly, smiling, and cheerful, but I could tell these weeks on hiatus had not been easy. He’d gained a bit of weight, his face was ruddy, he looked uncharacteristically stressed.

“You’ll still be here in ten minutes, won’t you? I’m afraid you’ll disappear. I have to go to the bank machine.”

He grinned, “I’ll try not to disappear.”

“Good! I’ll be right back.”

Walking familiar routes, none of them with a hint of vehicular traffic, was a joy beyond expressing. The touch-screen for the ATM was splotched with hand sanitizer, but the thing worked, and I practically sprinted back to market.

As I approached Fabrizio’s table, Riccardo Cambri appeared, solidly masked and hefting three bags filled with goods.

“Bello, caro! My god, it’s good to see you!”

Riccardo is indomitably bright. It’s more than simply a positive view of life, he lives with great and genuine enthusiasm, and spreads it around to everyone he encounters. I asked him how it was going.

“Wonderful! I’m teaching all forty of my piano students online, and they are practicing much more than usual, improving by leaps and bounds, and we will have a wonderful student concert this spring, even if it has to be on Zoom.”

“Bravo, maestro!”

“I am so happy and excited!”

From Fabrizio I replenished peanuts (shelled, lightly salted), almonds (with skins), dried apricots (un-sulphured, no added sugar), and lentils (green). The bill came to twenty-nine and change. He always rounds down. I gave him thirty, he gave me a one euro coin. I stammered my very genuine gratitude.

It was only much later, while reviewing the joys of the morning, that I wanted to return that coin Fabrizio handed me. Times have been hard for guys like him; one euro would not have meant much in the greater scheme of what he is probably facing financially, but it would have been a good thing to do.

In my eagerness to rejoin reality more or less as we’ve known it, I must also form new habits to accommodate reality as it manifests itself going forward. Perhaps next week I’ll stock up on a few new items and order a few more in greater quantities than I really need. Just because.

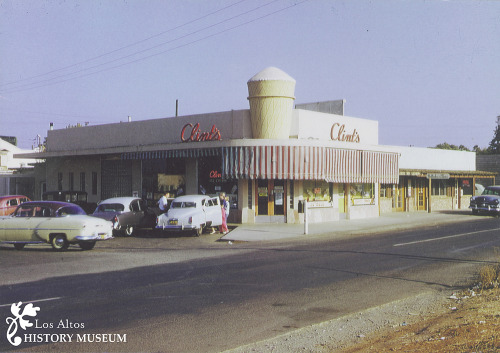

The photo is of market on a non-lockdown morning in 2015.