Italy had a kind of open house this past weekend. Nationally, over one thousand historic sites normally closed to the public, were, ostensibly, open for view courtesy of Fondo Ambiente Italiano, or FAI. Fourteen of those were in Orvieto.

“FAI” can be translated as “do it!” I chose to obey.

After a puzzling hour trying to navigate FAI’s vast, complicated, and beautiful website, I downloaded their app. A few of the historic sites I found listed there stood out; prime among them, Palazzo Simoncelli-Caravajal on Via Malabranca.

One evening in October, 2000 (my first time studying in Orvieto) I strolled in the rain towards Piazza San Giovenale to take in the panorama. I had passed Simoncelli-Caravajal many times. In daylight, through closed windows, you can just barely make out bits of a frescoed ceiling on the piano nobile (in American, the second floor). However, on that night, lights were on, and the view from the street revealed a ceiling riotous with color; beautifully preserved trompe-l’oeil. The windows were open, and someone was playing ragtime on a very good piano.

I stood under my umbrella; rainfall in the medieval quarter, glances of a baroque ceiling, and the loping, heart-beating rhythms of Scott Joplin. The pianist moved from one theme to another as twenty or thirty minutes melted into an instant. When there was finally a pause, I couldn’t help but applaud. Ragtime ceased. For the rest of my stay, the windows remained closed, the lights extinguished, the music absent. I blamed myself, of course, and regretted my impulsiveness.

All these years later, I still hope for ragtime when I pass the palazzo at night.

My friend Kathy lives a few steps from Simoncelli-Caravajal, so I asked if she wanted to join me on a tour. In front of the palazzo, a table with literature was set up alongside banners and knot of people. We were briefed on the building’s historical and architectural heritage. The palazzo – along with all the structures on FAI Orvieto’s weekend list – is the architectural product of the notably proficient Ipolito Scalza. It was stitched together from several medieval structures, ornamented with stone pediments and frames, and unified with plaster and paint. The guide for the pre-tour talk was a young woman, probably a high school student. She spoke with authority, ease, and clarity, then passed us on to the tutelage of another young woman of similar qualities.

We threaded our way upstairs and into a small drawing room. The room contained only one item; a baby grand piano. Could that have been the “very good” piano upon which the anonymous musician had inadvertently serenaded me those sixteen years ago? I like to think so. I gazed at it achingly. I wished I could play ragtime.

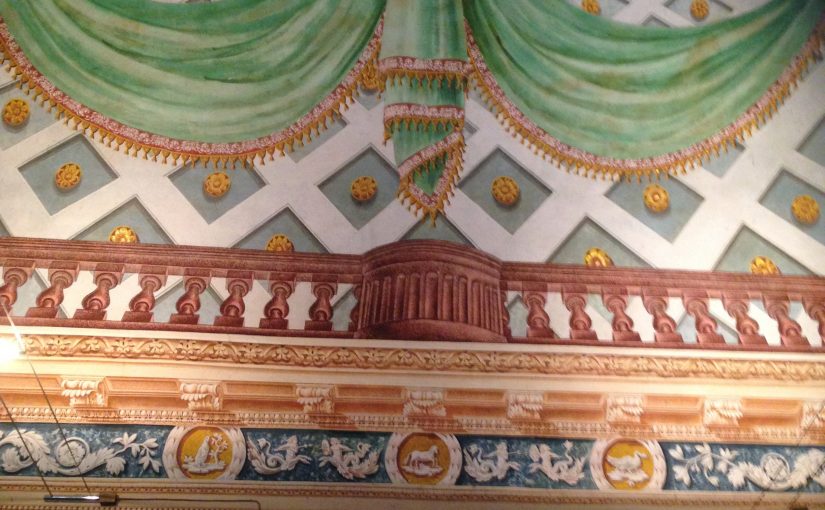

From there, we followed our guide into the grand salon. With the exception of a small patch that had suffered water damage sometime during the last four hundred years, the frescoes are as brilliant and pristine as I imagine they were at their unveiling. The architectural detail is all paint, but is so skillfully applied that even knowing the walls are flat, it’s difficult to believe that nothing is three-dimensional.

The pavement is covered, wall to wall, with a dance floor. That loping music I heard was for dance classes! Perfect.

Kathy and I visited other buildings, but none of them were open. Instead, each had several high-school age guides congregated in front, ready to offer history and analysis. They were relaxed, friendly, and prepared. None of the information they relayed seemed memorized, they showed genuine enthusiasm for their appointed facade, garden, or doorway, and were good-humored, and engaging. The excitement of moving on to the next site became about who we would meet to guide us.

Our final palazzo on Saturday was on Corso Cavour. We had just been given a thorough analysis of the facade of Palazzo Gualterio; how the grand entrance door had been moved from Palazzo Buzzi across town, and re-installed here. And how the deprived Buzzi then purchased another door to be moved from a third palazzo to install in its place. The guide pointed out all the ways the archway doesn’t fit into Scalza’s facade: the flanking windows are too close to the door frame, the cornice work on the facade breaks stride as it crosses the balcony, its height interferes with the second order of window frames, and so on. Then, because we asked where the palazzo on Cavour was located, she offered to walk us there.

We were greeted by another articulate and poised young woman who sported a variety of piercings. She guided us through an examination of the facade of Palazzo Guidoni, specifically noting its maritime imagery; shells, ropes, starfish, waves. The palazzo was supposed to have been open, she told us, but the contessa who lives there was not feeling well.

At that point, our guide turned us over to a young man in a yellow leather jacket who continued her story in English. He announced that in lieu of a tour with a healthy contessa, he had photographs. The grand ballroom we could not enter is surmounted by an actual dome of which there is no evidence from the exterior, and his photos showed it magnificently decorated with frescoes in pristine condition.

On Sunday, the only accessible interior we hadn’t seen was in Palazzo Monaldeschi. Until recently, the palazzo served as the Liceo Artistico, High School of the Arts. I’d passed the building many times, and on all sides, but had never understood that the various entrances all lead into the same interior.

To the south of the building, there is a large, fenced yard. At its head is a much-maligned, two-story arcade. That is flanked by architectural motley and distressed remnants of other arcades that offer little evidence of having been built according to a coherent plan. Opening directly onto the street to the west is an elegant and compact facade typical of Scalza. That design is carried off towards the east along another street.

The street entrance opens onto a large, decaying, interior courtyard, which, in its pre-high school days, may have been a cloister garden. The modern improvements are in worse shape than the bits of original structure that still show. We climbed stairs, followed a series of corridors, and were suddenly confronted by a grand salon with magnificent frescoes, which, to the right, surround an enormous fireplace. From there we moved into a pair of smaller rooms with coffered wood ceilings, a painted frieze below them, and below that the ugliest florescent light fixtures in history, now defunct.

It is filled with such interesting contrasts, this town, once the seat of popes and of wealth and power. It lives among its relics, converting them as needed to sustain their usefulness, never quite restoring them, but neither are they allowed to fall into ruin.

Guiding us through these shadows of former epochs, were beautiful, kind, articulate, poised, and stylishly dressed children of a time unimaginably different from the one they described. The highest thrill of those two afternoons of facades and ballrooms was not the masterworks of other ages, but the ease with which our young guides stepped across the chasm that separates them from their cultural past. They represent a treasure as wondrous as anything under the ailing contessa’s painted dome.