One of Orvieto’s most wonderful amenities is the Anello della Rupe – loosely translated, The Ring Around the Cliff – a footpath that encircles the city. Enter the Anello at any one of its five entrances, and you undergo an instant transformation from Urban Dweller to Woods Hiker.

Ring Around the Cliff – a footpath that encircles the city. Enter the Anello at any one of its five entrances, and you undergo an instant transformation from Urban Dweller to Woods Hiker.

Directly across a small piazza (now a parking lot) from where I live is Porta Vivaria. Of the old gate only the vertical posts and few stones of the arch remain. Originally, a steep road went from piazza to gate, and past it there were broad steps down to the valley floor. Small livestock were brought through the gate on their way to market in nearby Piazza del Popolo, thus the name “vivaria”. Popolo still hosts the mercato ai fuori every Thursday and Saturday, as it has for centuries (though probably not on the exact same schedule) but no chickens and goats, in case you’re wondering. Now it’s all clothing and cheese, produce and plants.

The path west from Porta Vivaria overlooks relatively recent excavations of one of the many Etruscan necropoli scattered throughout the area. The necropolis we’re passing now resembles a village of little cubes with roofs of sod, neat alleys, and sturdy stonework. I tried once to visit the site, but the gate was closed, or it seemed closed and I fell for the ruse. This day, there were visitors wandering around. I’d never seen that before, but it sent a clear signal that the park was open, so I went down to see if I could get in. Everything was unlocked, I paid my €3, and stepped back in time.

About half the tombs in this necropolis have been excavated, many of them “restored,” that is, missing pieces filled in with new material to stabilize the structures. You can walk around, go inside, touch, sit, breathe, and feel the centuries. It’s really great. The necropolis was build between 2,500 and 2,300 years ago, more or less. The display in the information center suggests that the tombs here were of middle class and upper middle class families rather than for aristocrats; that Velzna (the Etruscan Orvieto) was a relatively egalitarian society with a powerful middle class.

Then in between 300 and 270 BCE something happened. Here’re a couple of excerpts from a Roman source.

“These people were the most ancient of the Etruscans; they had acquired power and had erected an extremely strong citadel, and they had a well-governed state. Hence, on a certain occasion, when they were involved in war with the Romans, they resisted for a very long time. Upon being subdued, however, they drifted into indolent ease, left the management of the city to their servants, and used those servants also, as a rule, to carry on their campaigns. Finally they encouraged them to such an extent that the servants gained both power and spirit, and felt that they had a right to freedom; and, indeed, in the course of time they actually obtained this through their own efforts.

Hence the old-time citizens, not being able to endure them, and yet possessing no power of their own to punish them, despatched envoys by stealth to Rome.”

Rome, eager to please the estranged upper classes, engaged in “corrective intervention.”

This fascinates me. There is an historical hypothesis floating around that Rome was founded by the Etruscans. Without going into this too deeply, there is sense to it. Before the republic, Rome was governed by Tarquinian (Etruscan) kings or dictators. There are Roman histories to justify this oddness, but why would a bunch of Latin miscreants (for Romulus is said to have invited felons and exiles into his city to populate it) eager for freedom invite Etruscans to exercise absolute rule? Well, maybe they needed a kind of warden, but still.

The hypothesis goes on. During republican expansion, the powers-that-be began rewriting history to reflect a more patriotic Roman origin of the city, so Romulus and Remus and the She-Wolf were invented, and the Etruscan influence on culture, religion, and political structure was downplayed. After all, Rome was out to conquer Etruria, and you don’t do that kind of thing to your grandparents if you want to sleep at night. The solution? Change your grandparents. Rome’s was also a profoundly hierarchical society. It was only over time that reforms were made in governance that allowed the common citizen some say in policy and taxation, and slavery was a economic mainstay not to be tampered with.

So, what was going on with Velzna’s middle class that the Romans found so threatening? Were they experimenting with an egalitarian society at a time when the Roman Senate was feeling pressure from below? If Rome was primally Etruscan and the influence was still strong (and Velzna was now under Roman dominion), was this movement in Velzna a direct threat to the Roman power structure? I find the possibilities fascinating.

The archeology museum in town displays frescos that were lifted from one of the larger tombs in another necropolis southeast of the city. Those in the left chamber are of a kitchen staff cheerfully preparing a meal, while the frescoed right chamber shows the meal (possibly the funerary feast for the deceased) being served in a commodious dining room. With a few deft strokes, the artists captured personalities, body types, motion, relationship, and intention. There’s no attempt at realistic anatomical detail, but the figures leap across time; are startlingly familiar.

The paintings are familiar because of their sensitivity to the human form. They are also familiar because the Etruscans are still here, in Orvieto. There are a few people around town whose figures and faces could have been copied from surviving Etruscan art, if life really did imitate art (and who knows, maybe it does?) and many more, while less representative of the Etruscan ideal, still have the features.

Next, we come to Porta Maggiore, the Etruscan city’s only gate. The street that descends to the gate is called Via della Cava. It, and the gate, were cut into the rock by the Etruscans, and the gate’s supporting structure, the pavement, and perhaps a couple of temples in the area were then built from the stone quarried during the cut. When you walk the walls, you pass over the gate partly on original rock. The medieval (and no doubt the Etruscan) town grew up around Porta Maggiore. From there, the street climbs steeply to what is alternately called Piazza Sant’Andrea or Piazza della Reppublica (and casually, Piazza del Comune). Excavations have lead archeologists to conclude that the piazza has been in use as a market center since Etruscan times. The piazza’s eponymous church, Sant’Andrea, is placed on the foundations of both a Romanesque church and an Etruscan temple.

We continue on the Anello a short distance from Porta Maggiore, and arrive at ex-Campo della Fiera and Foro Boario. The Campo was further out for the Etruscans, both before and during Roman occupation. That site, about a kilometer away from the cliff, is being excavated and foundations of temples and official buildings have been uncovered. They suggest that Velzna was an important spiritual and administrative center, and that the Campo was used both for large regional markets and religious purposes. During the late medieval period, the market activities were moved closer to town. Foro Boario is the name for the cattle market that was also held here. These days, the area is occupied by a parking structure. Barely visible from the valley, it is an elegant piazza from the cliff.

Just past the Foro are the remains of the medieval aqueduct. A hugely ambitious project for its day, it proved to be difficult to maintain. Its history is one of boom and bust, emperor and pope, and ongoing rivalries between powerful families. It reminds me of how any collective effort requires rock solid political stability in order to sustain funding and organization. It’s easy to forget what remarkable times we live in, and how quickly they can dissolve.

Then for awhile, our walk is simply gorgeous. First we come to a row of houses along a bit of street called via (or strada) del Salto di (or del) Livio. The five buildings that look out over green gardens are, at most, a ten minute walk to your favorite coffee bar; shorter if you take the elevator that serves the garage. I’d love to live there.

Then for awhile, our walk is simply gorgeous. First we come to a row of houses along a bit of street called via (or strada) del Salto di (or del) Livio. The five buildings that look out over green gardens are, at most, a ten minute walk to your favorite coffee bar; shorter if you take the elevator that serves the garage. I’d love to live there.

The name of the street has a tragic, lovelorn history behind it. During the time of the Medici, Orvieto was riven by interfamilial strife. One of the warring families was the Sarancinelli who dominated the quarter now called Serancia, though the family probably took its name from the quarter rather than the other way around. Serancia sits on the cliffs above the street we’re passing now on the Anello.

One of the Sarancinelli was a young man named Livio who tried to set himself apart from the factionalism. By chance, he met a young woman visiting from Rome named Livia (cute, heh?) and they immediately fell in love. This was all very good and fine, but there had been a prophecy that predicted the extinction of the family should one of its members marry a Roman. So cousins of Livio (only thinking of the good of the family, of course) poisoned Livia, and she died three days later in the arms of her beloved. Livio fled to Rome, raised a militia, and returned for his revenge. When his attempts to kill the murders failed, he threw himself off the nearest cliff, and the area into which his body fell is called Salto di Livio; basically, Livio’s Leap.

I’d still love to live there.

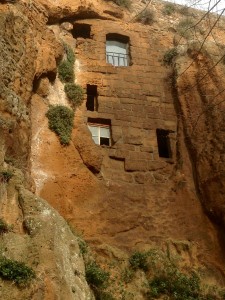

Then for another a kilometer or so we pass fascinating cliffs to the left, and to the right, rolling countryside, groves, and farms. The cliffs are fascinating because as they have fallen away over the centuries, caverns, caves, cisterns, rooms, and dovecotes have been revealed. Some of them have been filled in with masonry to prevent further erosion, others are left open, yet others have doors and window frames installed and apparently continued to be put to good use until quite recently.

The butte that Orvieto rests on is riddled with man-made tunnels, rooms, and cavities. The first were cisterns and storm drains carved out by the Etruscans. The Romans expanded these, the Orvietani who followed turned them into storage rooms, cellars, and trash dumps. The resulting labyrinth is comprised of over 1,200 chambers, passages, and wells. Many of Orvieto’s houses include a system of underground excavations that are still used to store wine, oil, and last year’s fashions. My realtor is always quite excited when a property includes caverne as we turn on our cellphone flashlights and eagerly descend.

The butte that Orvieto rests on is riddled with man-made tunnels, rooms, and cavities. The first were cisterns and storm drains carved out by the Etruscans. The Romans expanded these, the Orvietani who followed turned them into storage rooms, cellars, and trash dumps. The resulting labyrinth is comprised of over 1,200 chambers, passages, and wells. Many of Orvieto’s houses include a system of underground excavations that are still used to store wine, oil, and last year’s fashions. My realtor is always quite excited when a property includes caverne as we turn on our cellphone flashlights and eagerly descend.

I discovered early in my stay that going back into town via the next entrance constitutes a vigorous workout. One lengthy climb takes you up to three switchbacks followed by a hundred-fifty steps to street level. After my first ascent – which was, shall we say, not exactly in the manner of a mountain goat – I resolved (panting and sweating) to make the climb two or three times a week. I’ve been doing at least that, and my climbing abilities have improved, though not yet of goat caliber. At the top you’re rewarded, in spring and summer at any rate, with a rose garden. This entrance is named Palazzo Crispo-Marsciano. I like repeating the name. It’s fun. Palazzo Crispo-Marsciano. Palazzo Crispo-Marsciano.

“Crispo” was Tiberio Crispo, father of Pope Paul III. “Marsciano” was Ludovico dei Conti di Marsciano, a busy fellow who fought Turks for the Venetians and lead the Papal armies in Hungary. Now the palazzo is an office of the Tax Police. Really.

Next stop on the Anello, after a few more steep hills and valleys, is the double gate that abuts Fortezza Albornoz. In Etruscan times it was the site of a temple (what wasn’t?) that has been since named Augurale. Its first incarnation as a fort was a project of Cardinal Albornoz, a general and military advisor to Pope Innocent VI (a misnomer if ever there was one,) with a start date of 1364. It was destroyed in 1390, rebuilt in 1395, reinforced in 1413, and mostly destroyed except for the perimeter walls sometime later. Around 1527, Clement VII, concerned that if there were a siege he and his townsmen might run out of water, and having had a bad time of it when the French sacked Rome, began construction on Pozzo di San Patrizio. A remarkable bit of engineering, the well achieves a depth of 53 meters and is served by a double helix so that mules going down for water can keep right on going up again without meeting any of their descending brethren.

The fact that the gate next to the fort has several names, and is still known by all of them – each with authoritative historical roots – says something about Orvieto’s ability to tolerate contradiction, but I’m not exactly sure what. That I’m at all worried about the multiple names probably says something about me, too, and of that I can probably guess. The gate is variously called Porta Rocca, Porta Soliana, and Porta Postierla. I’ve even heard it casually referred to as Porta Albornoz and La Porta della Fortezza. The Outsider: I mean, really, people, we’ve had like a thousand years to work this through, can we arrive at a consensus, please? Orvieto: We need to? Why?

The fact that the gate next to the fort has several names, and is still known by all of them – each with authoritative historical roots – says something about Orvieto’s ability to tolerate contradiction, but I’m not exactly sure what. That I’m at all worried about the multiple names probably says something about me, too, and of that I can probably guess. The gate is variously called Porta Rocca, Porta Soliana, and Porta Postierla. I’ve even heard it casually referred to as Porta Albornoz and La Porta della Fortezza. The Outsider: I mean, really, people, we’ve had like a thousand years to work this through, can we arrive at a consensus, please? Orvieto: We need to? Why?

To the left, the Anello takes us over the funicular track, on through its woodiest section, and, after another couple of kilometers, back to Porta Vivaria.

The funicular was built in 1888 to connect the new railway line with the upper town. It was originally a hydro-balance system. Water was pumped into the upper car as it took on passengers, and out of the lower at the same time. Then a brake was released, and the two cars, connected to the same cable loop, switched places. The line was abandoned in 1970 (bad years for urban life everywhere,) electrified in 1990 and re-opened shortly thereafter. It runs every 10 minutes from 7:10 am to about 8:30 pm, thereby proving to be teasingly useless to morning commuters who have to catch the train to Rome that leaves at 6:57. Some things are universal.

Were we to continue to the right instead, we arrive in Scalo, the lower city, via a paved footpath  (paved a long time ago, so don’t picture asphalt.) Orvieto Scalo gets its name from the scales that used to weigh goods coming into and going out of town so they could be taxed. This was during the days of the Papal States. There are lots of interesting surviving oddities from those times in habit, law, custom, and cuisine. I’ll do a post one of these days.

(paved a long time ago, so don’t picture asphalt.) Orvieto Scalo gets its name from the scales that used to weigh goods coming into and going out of town so they could be taxed. This was during the days of the Papal States. There are lots of interesting surviving oddities from those times in habit, law, custom, and cuisine. I’ll do a post one of these days.

What I find particularly wonderful about the Anello is that you can decide to hike it almost on a whim. Enjoy a hearty lunch, stroll over to a bar, thro w down a caffe macchiato, and, wow! I feel like a walk. Let’s do the Anello! Minutes later you’ve left behind the urban crush, noise, and oppressive bustle of Orvieto (winky, smiley face,) and are surrounded by nature.

w down a caffe macchiato, and, wow! I feel like a walk. Let’s do the Anello! Minutes later you’ve left behind the urban crush, noise, and oppressive bustle of Orvieto (winky, smiley face,) and are surrounded by nature.

It was perhaps this sort of thing that inspired New York’s city planners to conclude that a central park would be a good idea. It is an excellent idea.

The joke that precipitated this particular blurt of writing was a simple one, which of course, makes the humiliation in missing it even worse. This guy went out with a bunch of people, people he likes very much, and their combined five little boys. They went to a new place on Piazza del Popolo, very stylish, very good, very quirky, very noisy.

The joke that precipitated this particular blurt of writing was a simple one, which of course, makes the humiliation in missing it even worse. This guy went out with a bunch of people, people he likes very much, and their combined five little boys. They went to a new place on Piazza del Popolo, very stylish, very good, very quirky, very noisy.

Last May, the nation-wide transition had already begun. Instead of trundling your recyclables to the ugly, dirty, domed containers that squatted in parking lots, you put a sack of a specific type of trash at your street door and a guy in a small hopper-truck came around the next morning and picked it up. My stay was short and I didn’t generate much trash, so details escaped me, but I knew it was a new sun dawning on the refuse horizon.

Last May, the nation-wide transition had already begun. Instead of trundling your recyclables to the ugly, dirty, domed containers that squatted in parking lots, you put a sack of a specific type of trash at your street door and a guy in a small hopper-truck came around the next morning and picked it up. My stay was short and I didn’t generate much trash, so details escaped me, but I knew it was a new sun dawning on the refuse horizon. speculated a late Christmas present (“late” was an American interpretation; it was before Epiphany and therefore would have been perfectly legal) but as I continued to the ground floor, I noticed that everyone had received these boxes. When I returned home, I took mine inside to investigate.

speculated a late Christmas present (“late” was an American interpretation; it was before Epiphany and therefore would have been perfectly legal) but as I continued to the ground floor, I noticed that everyone had received these boxes. When I returned home, I took mine inside to investigate. Because we are a palazzo with six apartments, we were given five, specifically sized and designed, color-coded and clearly labeled bins for the sorting of our refuse. The categories now are organic (in compostable bags,) plastic and metal (which is a clever combo, because we can include things like pharmaceutical blister packs,) glass, undifferentiated, and paper and cardboard. The bins live downstairs in the garage, and we wheel them out on the appropriate night as someone in the building remembers to do so.

Because we are a palazzo with six apartments, we were given five, specifically sized and designed, color-coded and clearly labeled bins for the sorting of our refuse. The categories now are organic (in compostable bags,) plastic and metal (which is a clever combo, because we can include things like pharmaceutical blister packs,) glass, undifferentiated, and paper and cardboard. The bins live downstairs in the garage, and we wheel them out on the appropriate night as someone in the building remembers to do so.

eto, and they remember what he likes to drink, his favorite things to eat, and even where he likes to sit! It’s amazing!

eto, and they remember what he likes to drink, his favorite things to eat, and even where he likes to sit! It’s amazing!

“It’s very good gelato,” says the man to no one in particular (his son is still across the street.) “There’s no better. I don’t know. This is bad.”

“It’s very good gelato,” says the man to no one in particular (his son is still across the street.) “There’s no better. I don’t know. This is bad.”